"Herb Score is the toughest pitcher I’ve faced. I just can't hit him."

— Mickey MantleBy Dave George

Palm Beach Post Columnist

LAKE WORTH – There is a way to tell the story of Herb Score that doesn't begin with the sensational lefty being struck in the eye by a line drive and, in that instant, forfeiting the kind of momentum that carried Sandy Koufax, his contemporary, all the way to Cooperstown.

You could start instead at a Dairy Queen that no longer exists in downtown Lake Worth, where Herb worked as a teenager and always made sure his friends got an extra scoop.

Or there's the grittier tale of Score getting backed over by a delivery truck as a toddler, which wound up leaving one of his legs slightly shorter than the other but, miraculously, changed little else.

And how about the crafty baseball scout named Cy Slapnicka who thought his days of relevance in the game were over until he left Iowa to warm his 66-year-old bones in Lake Worth and started hearing rumors of a neighborhood phenom whose squirrely fastball couldn't be timed or tamed?

It's a fat scrapbook of memories, with a state baseball championship for Lake Worth included, but there is one day above all days that people connect to Score's name. Might as well tell it right one time in his hometown, or at least as best as we can without input from Herb, who died in 2008 at the age of 75.

Lake Worth High School in the 1950s (file photo)

Truth is, he never really talked much about May 7, 1957 anyway. Didn't want it to have any power over him, probably. Didn't want it given greater weight than all the wonderful things that followed, certainly.

The scene was Cleveland's Municipal Stadium, a cavernous Depression-Era structure long since demolished and dumped into Lake Erie, piece by piece, to make an artificial reef. On this Tuesday afternoon, however, the place was alive and buzzing for a visit by Mickey Mantle and the defending World Series champion New York Yankees.

Cleveland Indians fans were more wound up than worried.

Their starting pitcher, 23-year-old Herb Score, was coming off consecutive shutout victories over the Yankees the previous season. In his two full seasons in the major leagues, Score had a 3-1 record against the game's most glittering franchise, with 54 strikeouts in 56 2/3 innings pitched against the Yankees, and with Mantle's endorsement as the toughest American League left-hander that he faced.

Overall, Score and a fastball that had to be 100 mph in the days before speed guns had pretty much everybody scared.

In 1955 he struck out 245 batters, which remains the American League record for a rookie and crushed the previous record of 227 set by Hall of Famer Grover Cleveland Alexander in 1911. Included in that total was a 16-strikeout game against the Boston Red Sox in which Score struck out the side in each of the first three innings.

(AP photo)

Dwight Gooden of the National League's New York Mets eventually set the major league record of 276 strikeouts by a rookie but it was 29 years later, in 1984. Dr. K wasn't even born by the time Score's career was ended, prematurely.

Like most kids, the old names and the old records probably didn't mean much to Gooden but try these on for size.

Koufax and Nolan Ryan didn't strike out 200 batters in a single season until they were 25 years old. Score had 508 in his first two seasons with the Indians. Over the same period, two full major league seasons at the start of a career, Steve Carlton struck out 330 batters and Roger Clemens had 312.

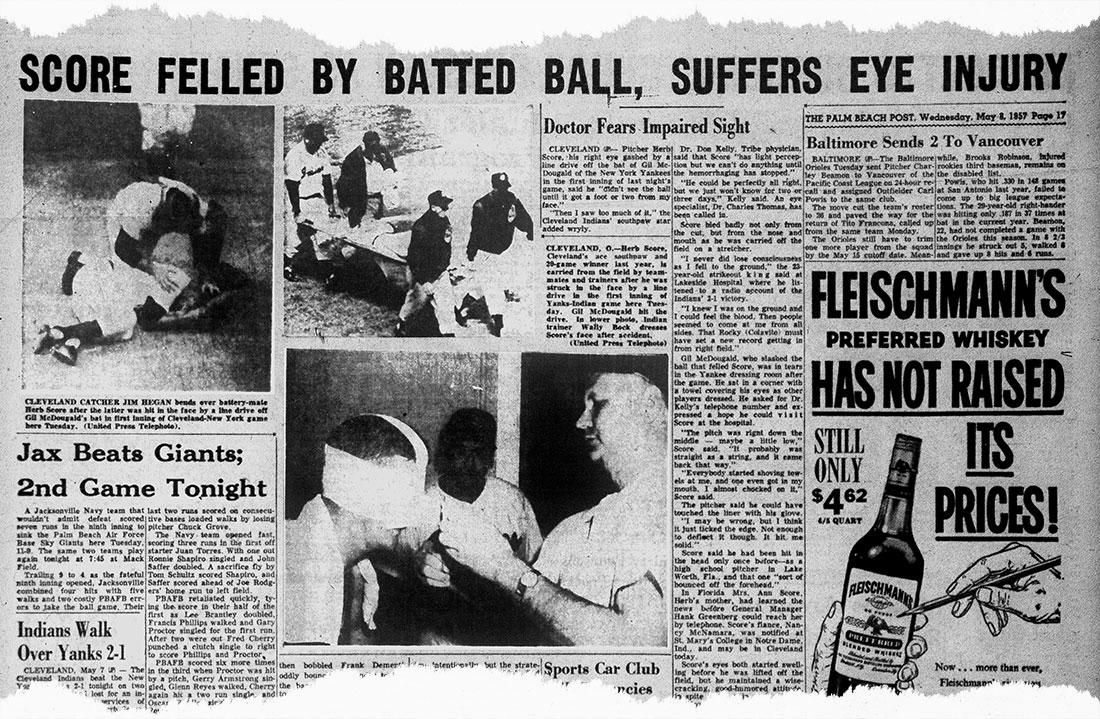

It was a line drive off the bat of Gil McDougald that stopped Score's rise. The Yankees shortstop was the second batter in that May 7 game, looking for a low fastball and slashing it right back from where it came. Score never had a chance.

The ball struck him flush in the face, bouncing so far that Cleveland third baseman Al Smith had time to gather it up and make the throw to first base for the out. Actually, Smith didn't need to rush the throw at all because McDougald didn't run the play out. Instead, he sprinted to the mound to see if he could do anything for Score.

Rocky Colavito, Score's roommate from the minor leagues on up, was there soon after. He sprinted in from his position in center field to place his glove under his friend's head as Score lay flat on his back, surrounded by shocked teammates.

"I didn't see the ball until it got a foot or two from my face," Score said later from Cleveland's Lakeside Hospital, his address for the next three weeks. "Then I saw too much of it."

Palm Beach Post sports page from May 8, 1957

News didn’t race around the world like it does now.

Herb's sister Helen, a government worker in Tallahassee at the time, didn't hear about the injury until later that night. The report, far too spotty, came over the radio while she was driving home from work with a basket of food she picked up at the drive-in.

Herb's sister Helen in 1957 (AP photo)

Herb's sister Helen in 1957 (AP photo)

"When I got home, a lady said my mother had been calling," Helen said from her home in Rabun Gap, Ga. "I got in touch with her and Mom said, 'It's bad, but he's got the finest doctors in the world and they will do everything that they can. You need to go down to the church and say your prayers for Herb, but more than that to pray for Gil McDougald. That man is a hurting man.' "

That story sounds right to any Lake Worth longtimer who knew Anne Score, who once felt such compassion for a Key West High School baseball team in town to play Lake Worth that she had the whole crew and their coaches over to sleep at the house, sprawled across furniture and plopped with pillows on the floor, so they wouldn't have to make the long drive home so late at night.

Anne was a single mom, long separated but as a devout Catholic never divorced from her husband, a New York City traffic cop. Herb, the oldest of her three children, was given the middle name of Jude, in honor of the patron saint of desperate causes.

Herb's mother, Anne in 1957 (AP photo)

Herb's mother, Anne in 1957 (AP photo)

Surely there were desperate times for Herb during his boyhood days in the Long Island town of Valley Stream, N.Y., not far from John F. Kennedy Airport and horse racing's Belmont Park.

His sister Helen remembers a couple of astonishing comebacks known well to family but never mentioned by Score in his adult years. He was by nature a quiet man but when it came to recounting and discussing the downturns in his life, Herb was an absolute sphinx.

"Herb was probably 2 ½ or 3 and he wanted to go across the street to play with friends," Helen said. "Mother was in the basement doing laundry, but she could look out the basement window and look across the street and tell him if it was all right.

"When he started to step out from behind a truck, and I can't remember if it was a milk truck or a bakery truck, all of a sudden the driver backed up and rode over him. They say his legs were severely injured. They put him in the hospital and put him in traction and apparently he was there for months."

Doctors wanted to operate but Anne resisted, asking for time to let the body heal. Finally, on the day before a difficult but seemingly necessary procedure was scheduled, she requested that one more X-ray be taken, just to make sure.

"Miracle of miracles," said Helen, "the bone was fusing. They never had to operate at all."

Then came the rheumatic fever, which kept Herb home in bed for months and cost him a year of grade school.

"That was another reason my mother gave consideration to going to Florida, so we could get away from the horrible winters," Helen said. "The rheumatic fever must have been about sixth grade. The doctor told her Herb would never lead a normal life in terms of hitting the ball in the street like the other kids did.

"She was relentless in the pursuit of getting him well, though, and she found a doctor who was aware of the properties of penicillin, which apparently had just come out. Whatever other therapies he used I don't know, but Herb came out a winner."

Before anything else could go wrong, Anne Score got busy on relocating her kids to Florida, not only for Herb, who was called "Buddy" by his family, but for little sister Ann, who also had health problems.

Father Thomas Kelly (AP photo)

Father Thomas Kelly (AP photo)

The first stop was Fort Lauderdale but jobs were hard to find. After a month, an opportunity opened up for a head bookkeeper at a West Palm Beach bank. It was August, 1949, and Anne Score needed a place to live. She settled on a small rental house on North D Street in Lake Worth, enrolled her two daughters at Sacred Heart Catholic School and sent Herb, a ninth-grader, over to make friends and try to fit in at Lake Worth High.

Nobody knew that the new kid could pitch. Herb himself didn't know until a priest named Father Thomas Kelly showed him how back in a CYO league in New York.

That's really when baseball became Score's life and he never forgot it. Years later, on July 10, 1957, it was Father Kelly who performed the wedding ceremony for Herb and Nancy McNamara Score at St. Mark Catholic Church in Boynton Beach.

Their wedding got moved up three months from the original October date because Score was rehabbing from the line drive disaster and wasn't playing at the time. Come to think of it, that incident changed just about everything, except for Herb's calm and likable demeanor. Not even being so horribly injured that some teammates had to look away changed that.

Herb Score and bride Nancy (file photo)

"They can't say I didn't keep my eye on that one," Score said on the day McDougald's line drive struck him down, and he said it before a medical crew had placed him on a stretcher and headed for the ambulance.

Nearby, McDougald was practically inconsolable, telling a teammate, "If he loses his sight, I’ll quit baseball. The game's not that important when it comes to this."

Between the immediate swelling around Score's right eye and the blood that was dribbling from the pitcher's ears, Cleveland teammate Russ Nixon almost couldn't believe what he was seeing.

"I've never seen a man look so dead," Nixon said in Terry Pluto's book 'The Curse of Rocky Colavito.' "He didn’t even flutter, and his face swelled up like a beehive."

(AP photo)

Score was rushed to the hospital, where he listened to the rest of the Indians' 2-1 victory on radio. McDougald called repeatedly for updates in the coming days, but the only relief he got was a phone conversation with Anne Score, who told the player it wasn't his fault and that everything would be all right. For years to come, whenever McDougald was in South Florida, he made it a point to stop by for a visit with Herb's mom.

Everything was not all right, however, at least not immediately, though Score also tried to lessen the anxiety for McDougald, who batted .289 that season but soon retired at 32 when his own numbers dropped off.

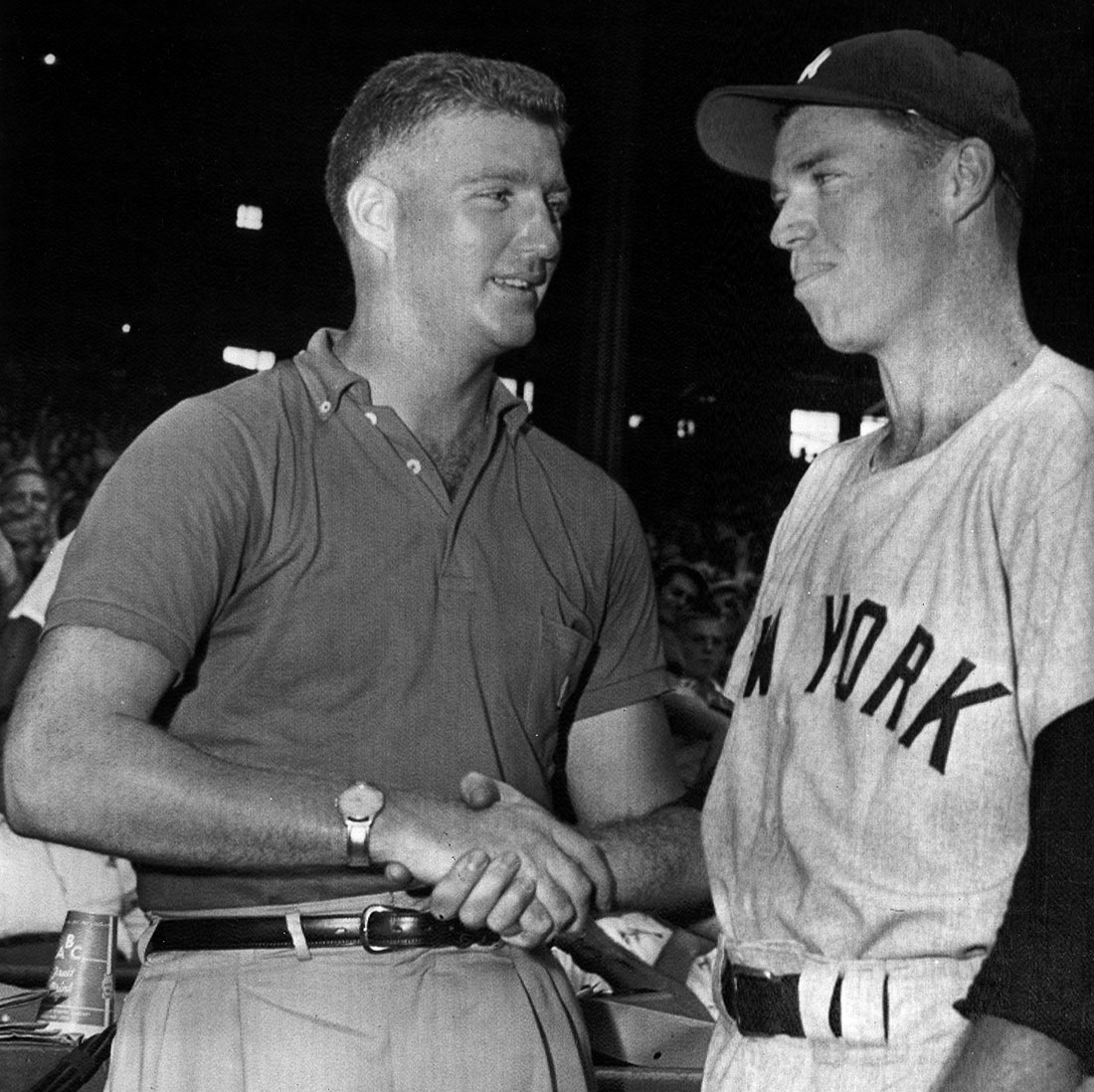

Score with Gil McDougald in 1957 (AP photo)

"I talked to Gil and told him it was something that could happen to anyone." Herb said. "It's just like a pitcher beaning a batter. He didn't mean it."

Score spent three weeks in the hospital as surgeons carefully worked through a list of injuries that included a broken nose, a lacerated right eyelid, damage to the right cheekbone and, of course, an undetermined amount of damage to the right eye. Seconds after the ball struck him, Score asked if the eye was even there. Once at the hospital, his head wrapped up like a mummy, Score was ordered not to move his head at all.

Mrs. Anne Score arrives in Cleveland, from Lake Worth, to see Herb in the hospital.(AP photo)

Mrs. Anne Score arrives in Cleveland, from Lake Worth, to see Herb in the hospital.(AP photo)

"They wouldn't let him blink his eyes," Helen remembers. "They didn't want any pressure in that area."

Doctors didn't want any visitors, either. An exception was made for Nancy, Herb's fiancée, who hurried over from St. Mary's College in South Bend, Ind., where she was a senior. Herb's mother, Anne, waited a week, not wanting to alarm her other children or friends in Lake Worth, who had been assured the situation was not dire. Anne met with reporters at the Cleveland airport with the happy look of a woman on vacation.

She, like Herb, always tried to tamp down the trauma.

•Carroll Webb was one of Herb's best pals on the Lake Worth baseball team. Still, he didn't learn of the childhood illnesses and accidents that challenged Score until years later, when Webb married Herb's sister, Helen.

Carroll Webb

Carroll Webb

"Herb never mentioned any of that," said Webb, who went on to become a lawyer and a Florida state legislator. "He had kind of a reserved way about him. He was very friendly, not aloof, but you just knew there was a discipline from which he was not going to deviate. I never heard him use a curse word or even a slang word like dadgum or darn, and he never showed any sign of 'I'm the star.' "

That doesn't sound much like 2015, but then neither does the Lake Worth of Score's high school years, when graduating classes numbered less than 100. Nearly 2,400 students attended during the 2013-14 school year.

Dennis Dorsey, a former classmate of Score's and a former mayor of Lake Worth, said "the average age of Lake Worth in 1953 was 59.8. That was higher than St. Petersburg but they had more people. It was healthy at that time, because you had a lot of people who would volunteer, taking part in civic clubs and churches and school affairs."

It was a world without malls, so Lake Worth teenagers might hop the bus on a Saturday for the ride up Dixie Highway to West Palm Beach, where you could get a hot fudge sundae at the Walgreen's and spend the afternoon shopping on Clematis Street. A trip to the beach and Lake Worth's Casino pool was a long walk across the bridge, unless a kid could scrape up enough money to rent a bike from the shop on Lake Avenue. And, one way or another, everybody found their way to The Duke, a drive-in restaurant on the main drag south of downtown.

What Herb wanted most to know, however, was where did the local kids play baseball? He immediately got a spot on the Trojans varsity team, even as a freshman, and pitched a no-hitter in his first game against a Pompano Beach school called Riverside Military Academy.

Score and Dick Brown in high school

Score and Dick Brown in high school

"The following week, he pitches batting practice and it's no fun," Webb said. "Coach (John Golden) realized it and I think that was the last week he pitched BP. When he threw, he threw. He didn't let up in BP or a game.

"I remember stepping in one time against him and you couldn’t even see the ball."

Catching it was worse, in some ways. Lake Worth's catchers began shoving sponges inside their mitts to reduce the pain. It took another future major-leaguer, Dick Brown, to handle Score's fastball well.

Larry Brown, Dick's brother, also played in the big leagues for 12 years but he was five years younger. For him, watching the 6-foot-2 Score mow down the high school competition must have made an even bigger impression. The experience of playing at the top level himself, however, gives Larry's opinion great credibility.

Score with former major leaguer Larry Brown. (AP photo)

"They didn't have a speed gun back then," said Larry Brown, 75, who lives now in Wellington, "but when you get up to that level, the naked eye says 'Wow.' He had a great curveball, too. That thing would drop 3 feet in the dirt. I remember one game my brother was catching Herb and they were playing Vero Beach. Their players were making bets on who could foul a ball off."

"He was going to be a Hall of Famer."

It didn't happen, but the wonder of those Lake Worth days remains, including the fact that Score was a star basketball player, too, specializing in a deep corner shot that would count for three points today.

The Trojans played their baseball games on campus back then, with bleachers backed up against the outside wall of the old gymnasium. Right field reached all the way to the football stadium. Some of the football bleachers actually had to be removed each season to make room for the diamond.

Score pitched six no-hitters for Lake Worth and averaged two strikeouts per inning. He was 8-0 in his final season with the Trojans, with a couple of 17-strikeout days. The games were only seven innings, too. The only problem for Score, and it was a serious problem for batters, too, was his wildness. In one game against Fort Pierce he struck out 14 hitters and walked nine more.

Through it all Slapnicka, the crusty old scout, worked his own kind of magic. He was known as the man who discovered Hall of Fame pitcher Bob Feller, a huge star in Cleveland, and Slapnicka steered Herb toward the Indians, too. Constantly he haunted Lake Worth games. Frequently he took Herb out to dinner or dropped by the house to hobnob with the family.

Score with Cy Slapnicka in 1956. (file photo)

There's no telling how many other scouts were around when Lake Worth headed into the 1952 state playoffs on a championship run. Score pitched the first of the three games that were needed to take the Class A title at Fort Pierce's Jaycee Field. He was not himself, however, drained by a viral infection and throwing up behind the dugout between innings.

Didn't matter. Score let three runs score on wild pitches but he still beat Bronson 4-3 with 14 strikeouts and just one hit allowed.

Don James did the heavy lifting after that. He worked four innings of an easy win over St. Paul's of St. Petersburg and 10 more in an extra-inning clincher, with Lake Worth beating Cocoa 3-2. James worked 14 innings over two days because Score was too sick to go on.

One more game remained, a trip to Lakeland to play Class AA champion Miami Edison for statewide bragging rights, but the best Score could do was a late-inning relief appearance in a 5-4 loss.

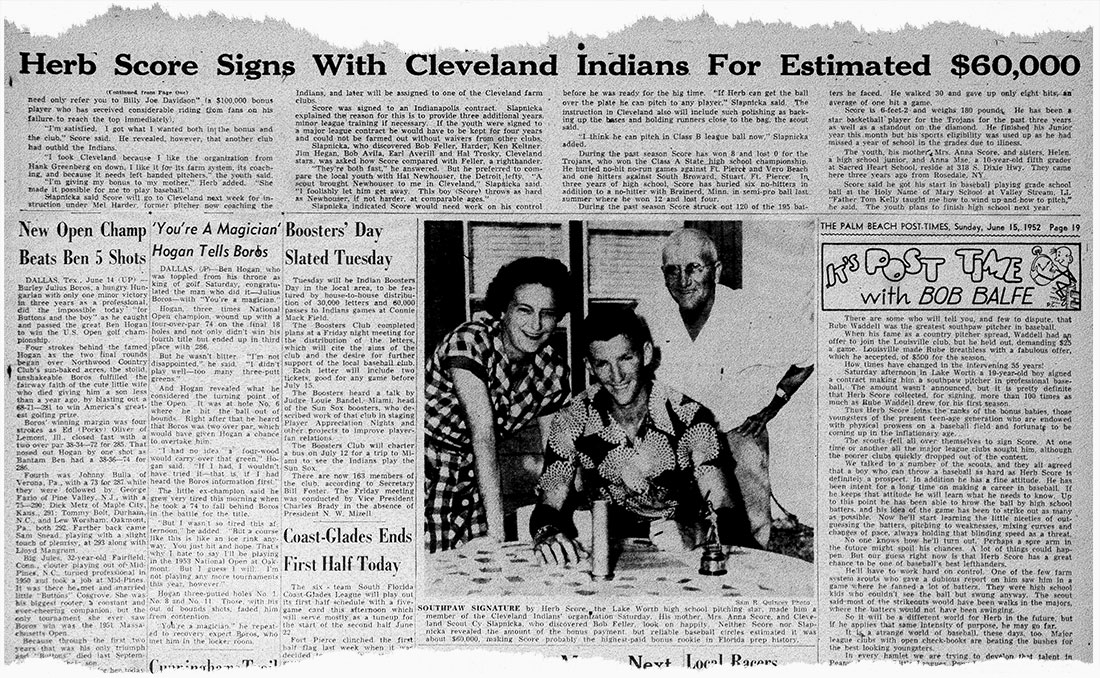

The Trojans headed home in a caravan of cars the next day, a Saturday, figuring the excitement was over. Then came the Sunday Palm Beach Post with the front-page news that Score had signed with the Indians, and for the spectacular sum of $60,000, a fortune half a century ago. Score said later that a few other teams had offered $100,000 but he wanted to stay with the Indians.

The Palm Beach Post on June 15, 1952.

"He gave the money to my mother," Helen said. "We had lived in a house on Dixie Highway but she bought a house over on South M Street. Not a large house. Just two bedrooms, but we built on the back of that house a breezeway and a master suite and a bathroom that could be Herb’s when he came home from playing ball."

Score was 19 and not quite finished with high school because of falling behind schedule due to the year claimed by boyhood illness. After a quick summer fling with Double-A Indianapolis, with 62 walks in 62 innings proving how raw Score still was, he returned to Lake Worth to finish up classes and get his diploma.

"Discipline," said Helen, "is one of the things my mother expected."

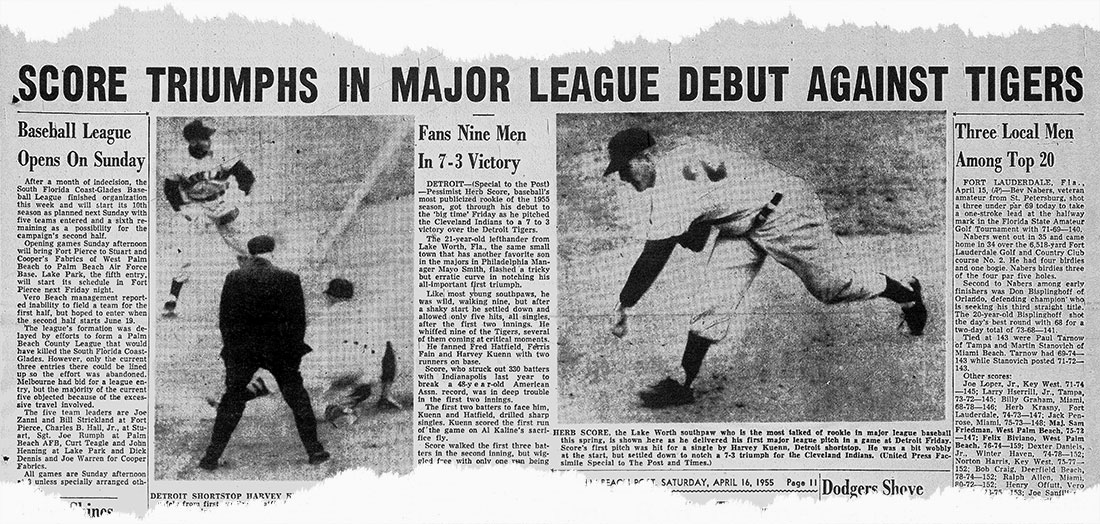

The Palm Beach Post of April 16, 1955

In a flash, at 21, Score was with the big club, still walking too many batters but getting so many strikeouts that nobody cared. He joined a Cleveland team that was coming off a World Series appearance and featured a pair of 23-game winners in Bob Lemon and Early Wynn plus the legendary Feller, still getting people out at 35. All three of those pitchers wound up in the Hall of Fame.

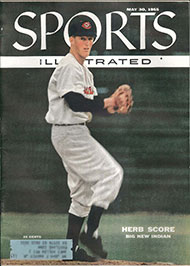

Sports Illustrated cover from May 30, 1955

Sports Illustrated cover from May 30, 1955

All the same, Score was an instant phenomenon. The papers called him "Hurricane Herb." Ted Williams said he was the toughest left-hander he faced. Score backed it all up, too, by pitching seven shutout victories over his first two major-league seasons and leading the American League in strikeouts each year. Oh, and Score scored the cover of Sports Illustrated, too, in the midst of that Rookie of the Year ride.

Season three, 1957, was supposed to be more of the same, and then on and on stretching all the way to Cooperstown. The Boston Red Sox offered to buy Score's contract for $1 million that spring but the Indians refused, even though entire teams could be sold for $4 million in those days.

Then came that McDougald line drive.

•Score's career didn't end that day just one month short of his 24th birthday, and neither did his love of baseball.

He returned to pitch two more seasons in Cleveland and two-plus for the Chicago White Sox, never regaining that intimidating presence on the mound but never blaming the psychological or physical damage of the 1957 incident, either. It was arm trouble that first developed on a cold, rainy night in Washington, Score said, and that's when you could get him to talk about it at all.

Before the line drive, he was 38-20 with a 2.63 ERA. After it he was 15-26. A change in his delivery, moving away from the long and aggressive follow-through that left his back to the plate and his head exposed, likely contributed to the decline in numbers.

"I hit against him when he was trying to make it back," Larry Brown said. "Herb had just got sent down to the White Sox farm club in San Diego and I was playing for Salt Lake City in the Pacific Coast league. He did not throw the same. He had pretty good velocity but he didn’t have the pop on that fastball. Fairly good hop, but not real pop."

Suddenly it was over for Score, at the age of 30.

The Palm Beach Post of April 8, 1963

"He had a chance at becoming as good a lefty as there ever was," Colavito said years later. "He had that kind of stuff. He had hard knocks, but he never complained. You had to respect him for that. I loved him like a brother."

The Indians must have felt the same way because they didn't hesitate to give Score another opportunity to help the franchise.

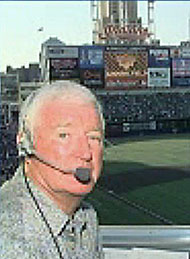

They immediately hired Herb to be the voice of the Indians on TV and later on radio, and without a speck of training. He wasn't quite a natural at it but Clevelanders didn't want a smooth operator. They wanted Herb, the superstar who acted like nobody special and who obviously was pleased still to be a part of it all.

Herb Score in the Jacobs Field broadcast booth

Herb Score in the Jacobs Field broadcast booth

That's the way Ohio fans know him best, a neighbor who lived for decades in the Cleveland suburb of Rocky River and is buried there, and a good sport who endured countless losing seasons by the Indians with optimism and good humor.

It was a job that lasted 34 years and brings the tale all the way back to South Florida.

Score's last broadcast was in Miami, where the Indians lost Game 7 of the 1997 World Series to the Florida Marlins. "It's just time," Score said of his retirement. He was 64 and over a lifetime had worked nearly 6,000 Indians games on the field and the in the broadcast booth.

His marriage to Nancy lasted 51 years. He proposed at The Duke in Lake Worth, where they were sharing a drive-in restaurant meal in the car after catching a movie.

"It's been a long time," Nancy said recently. "It probably was a matter of him saying, 'Would you like to be my wife?' and me saying, 'Yes, but you better talk to my dad.' "

Nancy was his unquestioned angel all the way, caring for Herb through the trials of an auto accident that banged Score up pretty good in 1998 on his solo drive to their Fort Myers winter home. He had been in Akron the previous night to be inducted to the Broadcasting Hall of Fame in Akron, Ohio.

Score bounced back to the point where he could throw out the ceremonial first pitch at the Indians' home opener in 1999 but the long-term issues from the accident never quite left him. He lost some of his mobility to a stroke in 2002 and died after a long illness.

There's a way to tell the story of Herb Score, though, without ending it on a down note. Here it is, as bright as the sunny days he once spent in Lake Worth, throwing the ball so blindingly fast that he could just as easily have faked everybody out by keeping it in the glove.

First, a quote from Herb that he sometimes gave when others wanted to wallow in what never was. "I'm a lucky fellow," he said. "I'm glad God gave me the ability to throw a baseball well for a few years. That drive could have killed me."

And last, a joke from 1977 told by former Indians infielder Buddy Bell, included here because it was so emblematic of Score's natural, lasting impact on everyone who knew him, from Lake Worth High classmates to major-league teammates to generations of Indians fans.

"Herb is such a nice guy," said Bell, "he probably makes the bed in his hotel room in the morning."

Anne Score, the mother who chose the long-ago cottage community of Lake Worth as the perfect place to raise her family, would have liked that. She would have expected it, too.