By Joe Capozzi

Palm Beach Post staff writer

Photography by Thomas Cordy

She was driving up Interstate 95, headed to a Christmas reunion in New Jersey, when she got the call.

You need to know that your son Brian is doing heroin.

"I had to pull the car over and throw up," Penny Grieb said, recalling that day in 2011. "I got sick because somehow you know that this might be the beginning of the end."

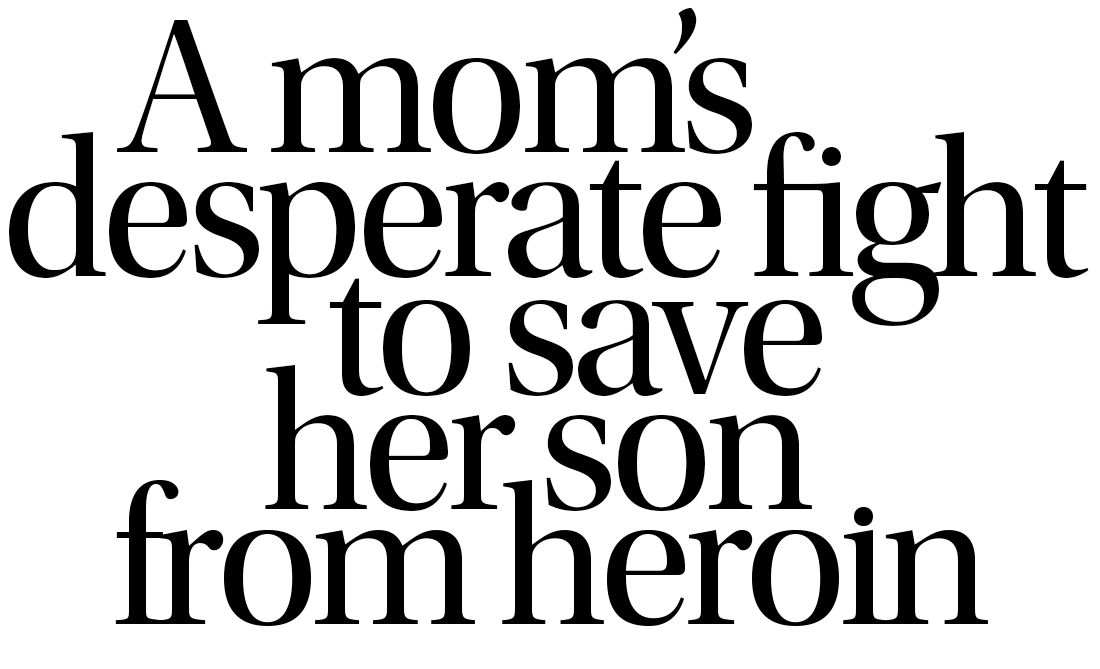

For years, Penny and her husband, Rich, had lectured their three kids about the danger of drugs. She knew Brian, their middle child, had struggled with an addiction to pain pills after a knee operation in high school in 2008.

— Penny Grieb

But now he was sticking needles in his arm and injecting heroin?

Penny vowed to channel her desperation and fear into a pledge, a mother's obligation, to do whatever it took to save her son. She would end up attaching a tracking device to Brian's car, confronting his drug dealers and even concocting a plan to kidnap him and chain him up at the family's summer cabin in Maine.

But mostly over the next four years there would be constant fighting and denials, daily rituals of rooting through closets and flipping the mattress in search of needles, syringes and folded-up squares of waxed paper. They'd ferry Brian to doctors and treatment centers, hold family interventions, kick him out of the house and take him back.

Finally, there was hope. In January 2015, he'd agreed to leave his destructive environment to go into detox and treatment far from home. They sent him to a place Penny thought would help him get clean — Palm Beach County.

Five months later, he was dead. He had locked himself in the bathroom of a Delray Beach sober home and overdosed on heroin, a month before his 25th birthday.

Once again, the news came to Penny and Rich through phone calls, devastating gut punches, the last one dropping them to the kitchen floor.

Brian overdosed… He's been taken to the hospital… They're working on him…

And a bit later…

I'm so sorry, but he's gone.

Hours before he died, he'd pleaded to come home, but Penny insisted he stay in Florida for long-term treatment.

More than a year later, Penny and Rich are consumed by guilt because they failed to save their son.

They wonder how he was able to sneak heroin into a sober-living house and whether rescue crews did enough to save him.

They're angry at the Palm Beach County Sheriff's Office, claiming deputies were so insensitive to Brian's case that when they shipped his belongings home to South Carolina they mistakenly sent a dose of heroin. (It was tucked inside his wallet, in a tiny pocket investigators missed.)

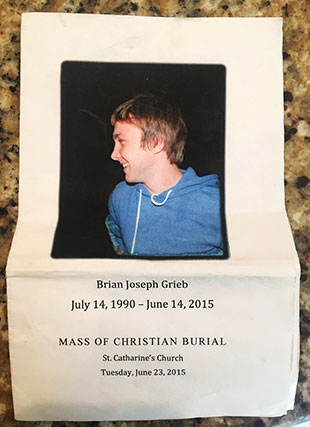

Most of all, they're determined to sound the alarm to an epidemic with no end in sight. They want to put a face — their late son's face — on a disease whose victims are too often dismissed as drug addicts getting what they deserve.

They also know their family's battle isn't over.

Their youngest child, Jessica, is addicted to heroin, too.

I want people warned: 'You are at war with heroin'

In 2015, a person died every other day of a heroin-related overdose in Palm Beach County.

Brian Grieb was one of them.

His mother takes no comfort in knowing she is not alone in her despair. In daily visits to blogs and websites devoted to parents of children addicted to heroin, she reads the same desperate plea over and over:

"My child is MIA" — missing in action, a term entirely appropriate, she said, for the emotionally bruising combat waged on families by addiction.

"You are at war with heroin," she said.

And she is fighting back. But she said she can't do it alone. She hopes to persuade other grieving families to speak out and shatter the stigma that, according to Penny and other families of addicts, has hindered a proper response to the epidemic.

"If we don't start talking about this, nobody is going to do anything about it," she said.

"I really just want to scream at the top of my lungs. I don't care that they know my son died of a heroin overdose. I want people to be warned."

She knows she will be judged by people who don't understand addiction, by parents who wonder how she could have allowed two of her three kids to fall into the grips of heroin.

She said she doesn't care about the critics, who include her own relatives and close friends, people from whom she is now estranged.

They haven't seen how heroin can breach the sanctity of a solid upper-middle class community like Pawleys Island, S.C., known for hammock makers and seaside vacation rentals, where drug dealers delivered heroin — "as easy as ordering pizza"— to Penny's house by tying it to a rock and tossing it from a moving car onto her front lawn.

"We've heard it, unfortunately, too any times: 'Couldn't you have done more?"' she said. "Well, I don't think so. I don't truly think I could have done more. I did everything I could."

She has at least one ally, someone on the epidemic's front lines: Her daughter, Jessica, a recovering heroin addict whose boyfriend, a close friend of Brian's, died of an overdose eight months before Brian died.

Jessica, 24, has been in treatment in Palm Beach County since 2014. She said she has had a few relapses since her brother's death but has been clean since Feb. 12.

"When we lost Brian, I knew I couldn't go back to that," she said. "I thought about my mom, my family. I realized it's going to end up killing me, too. I can't let that happen."

Jessica lives in Lake Worth and works at a treatment facility.

"One thing that helps keep me clean is knowing I can help another person," she said. "I can let my brother's story live on through me by helping others."

'I want the world, Chico, and everything in it'

Brian Grieb is everywhere in his family's two-story house in the coastal lowlands between Charleston and Myrtle Beach, the one with the inviting front porch tucked under skyscraping slash pines, on a rustic cul-de-sac just off Otter Run Road.

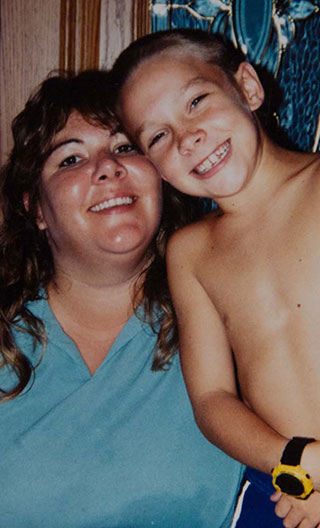

He smiles back from framed photos on the wall, as a child, teen and young man.

Penny and Rich can still see him working on the tile back splash in the kitchen, laying the hardwood floors in the dining room, building the concrete driveway out front, just a few of the projects he helped his dad with after the family moved to Pawleys Island from Spring Lake Heights, N.J., in 2009.

"You cannot walk through the house without seeing the work that Brian helped do," Penny said.

He's in the living room, too, sitting over the chess board where he schooled so many opponents. He liked to stand up and slide the final piece, saying "checkmate" as he walked away — "Just to piss me off," his older brother, Richie Jr., said with a smile.

Brian attended a local college. With his knack for numbers, he was payroll manager at Coastal Staffing, a company started by Penny's father 20 years ago to help staff the paper and steel mills in nearby Georgetown.

— Penny Grieb

His sister remembers him for his "random acts of kindness." He'd play Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtle games with his young cousin, Mac, and mow the grass of elderly neighbors.

"He loved anyone under 6 and over 60. That was his motto," Penny said.

He wrestled in high school, participated in a future business leaders group and always seemed to have the prettiest girl on his arm. His favorite group was the Red Hot Chili Peppers.

"He loved to wink at you, especially as he was leaving a room," Penny said.

Among his unique talents: Quoting favorite movie lines during conversations. If someone tried to impress him with a story, he might tap Austin Powers and reply, "Woop-dee-doo, but what does it mean, Basil?"

What would you like for lunch, Brian? "I want the world, Chico, and everything in it," he'd say, quoting Scarface.

He loved Breaking Bad, about a high school teacher who becomes a methamphetamine kingpin, and Mad Men. "He could relate to Don Draper," his older brother Richie said about the Mad Men lead character who partied hard yet came to work every day.

In the late spring of 2015, Richie was working in New Jersey when he received a random text from Brian: ''DAA-da… DAA-da… DAA-da…"

At first, he had no idea what it meant. "Then I started saying it over and over, and it hit me: It was the beginning of the Mad Men (theme) song," he recalled, laughing.

Richie texted back his own phonetic translation of the song's final notes, when Draper's falling cartoon shadow lands on the couch.

"Those were the last words we ever spoke," he said.

Started with pain pills, but heroin? Not going to happen

Brian had his demons, too.

At Manasquan High School in Spring Lake Heights, N.J., he lost a few friends in a rash of suicides in which students jumped in front of commuter trains. He refused to talk about it.

He drank beer and experimented with marijuana in high school, but his parents never worried it would lead to heroin.

— Penny Grieb

"It just wasn't even a thought. If you had told me 10 years ago that my son would be sticking a needle in his arm, I would have told you you're crazy. That's never going to happen," Penny said.

"When my children were growing up, his father and I always stressed the importance of staying away from drugs, especially heroin."

She said it never dawned on them to teach their children about the danger of prescription pain pills and how addictive they could be. "I guess maybe because we didn't grow up with that," she said.

Not long after arriving in South Carolina in August 2008, Brian twisted his knee running through a field one night with friends. He had surgery to repair three torn ligaments.

During his recovery, he was prescribed Percocet for the pain. "At one point, his father realized it was a problem and actually took it (away) and started being the one to make sure it wasn't being abused," she said.

Despite his dad's vigilance, Brian became addicted to pain pills, which he later told his parents were readily available around town.

"My children said that when they go out to a bar, it's just a given that somebody is going to offer to sell you a prescription drug," Penny said.

"As Brian explained to me, you take it to have fun that night and to party. And the next day you are hung over, so then you take it to feel better. And then every day you are taking it just to feel better. And before you know it, you are taking 10-15 pills a day."

"And that gets too expensive. Then your friendly local drug dealer says, 'Hey, I've got something else that's just as good, and it's a lot cheaper.' And that's where they make the switch."

Your child is using heroin: 'What do we do now?'

Exactly when Brian first tried heroin is not clear. But his family believes it was some time after they arrived in Pawleys Island.

The family left New Jersey to be closer to Penny's parents because Rich had developed avascular necrosis, a disease that deteriorates the bones in his back and hip. The move was hard on Brian and Jessica because it abruptly dislodged them from "The Heights Crew," as their tight circle of high school friends was known.

In those first two years in Pawleys Island, Brian lived at his family's house with his girlfriend. They went to work every morning. They cooked meals and ate dinner with his parents at night. They cleaned up around the house.

Penny and Rich later learned that Brian would shoot up in his bedroom upstairs after his parents went to sleep in their first-floor bedroom. But he always woke up on time for work every morning.

"He kept it very well hidden," Penny said. "They didn't go out a lot so there wasn't that 'Oh, my god, you are coming home at 2 in the morning. What have you been doing?"'

Then, in December 2011, Brian and his sister drove to New Jersey to spend Christmas with relatives. Their parents planned to follow them a few days later, after Rich went for a doctor's appointment to get treatment for his back.

Penny said she was driving near the North Carolina/Virginia border when she received that gut-wrenching call from her sister-in-law saying Brian was using heroin. He was nodding off in front of relatives and sweating, she told them. Jessica said she found a needle and spoon in the back of the car.

"It was very strange to hear them tell us that. These were things that we never saw him do," Penny said.

The lives of the Grieb family changed forever that day.

"When you find out your child is doing heroin, your world, it just implodes," she said.

"I remember thinking, 'What do we do now?' There are no instructions."

'It's not your son. It's this monster.'

For Penny and her husband, the "new normal" became endless hours on the phone with insurance companies and treatment facilities, trips to doctors' appointments, standing in long lines for Suboxone, a drug that blocks the effects of opioids, and searching his bedroom for drugs.

— Penny Grieb

"I can't tell you how many times I flipped over a mattress in the past four years," she said.

When they caught him, there would be arguments and denials. "Don't worry, mom, I've got this," he would say. "No, Brian, this has got you."

Brian always thought he could control his habit, Penny said. "It wasn't anything he was addicted to, in his eyes. He didn't have to do it all the time. He could do it once in a while. Then once in a while became more and more."

He was able to get clean. He could do that for a week or two at a time, but he'd always start using again, Richie says, describing his brother as a classic "functioning addict" who could take just enough for a desired high and still be productive at work.

"Brian was a committed addict. He was diligent. Sometimes even mature with it," his brother said. "It was very deceiving, not only for him but for everyone else."

In 2014, Brian stayed clean for six months and took care of his mother, who was bedridden with a serious illness. When she got well, he started using again.

They would throw him out of the house. He spent nearly a year with his girlfriend's family in Georgia and at one point, he lived out of a car. Eventually, they took him back.

"It's very difficult to not enable your child," she said. "When you do kick him out, that's where your real torture begins because then you lay there night after night wondering, 'When is my phone going to ring? When am I going to get that phone call?"'

She chokes back tears as she describes how heroin eroded her son's charisma into something dark and moody.

"When he was using, you have a different person. It's not your son. It's not your daughter. It's this monster. And it's not anything they are doing evil or wrong. It's the disease."

Getting heroin is 'easy as ordering pizza'

In her desperation to help her son, Penny started acting, in her own words, "crazy" and "nuts."

"When your child is an addict and you are chasing them down the street when they are driving away and you are trying to stop them, you start to think, 'What can I do? If I can't get him into treatment because he won't go, what else can I do?'"

One idea she seriously considered: Kidnapping Brian and taking him to Maine. "Lock him up in our cabin in the woods," she said. "Chain him up and make him get better."

— Penny Grieb

She relented when her husband explained she could wind up in jail.

They put a tracking device on his car to see where he got his heroin. One time it was a grocery store parking lot.

Other times, she said, she followed Brian in her husband's truck and parked it outside a house "in a very nice neighborhood." She took photos of teenagers pulling in and out of the driveway.

One day, a young man came out of the house and cursed at her to leave.

"He threatened to call the police," she recalled. "I offered him my phone. I said, 'Here. Call the police. I'm begging you.' He flipped me off and went back inside."

She wanted to put fliers in mailboxes on the street, alerting neighbors to suspected drug activity at the house. But she said her husband wouldn't let her, fearing drug dealers might hunt her down and shoot her.

She called the local sheriff's office and complained about the house. "They told me they knew and to just try to keep my son away from there," she said.

But the heroin still found its way to her son's bedroom.

"It's as easy as ordering a pizza," she said. Drug dealers "will deliver it to your house. They will throw it on your lawn for you. It's amazing that nothing is being done."

The final 'I love you'

Finally, in January 2015, Brian agreed seek help in Florida. His sister, Jessica, had gone there for treatment a year earlier on the recommendation of a close family friend, a recovering addict who works for a treatment center.

Penny said she knew Jessica had had a drinking problem, but she kept her heroin use hidden from her parents, as Brian had. Unlike Brian, Jessica actively sought treatment to get clean as early as fall 2013, Penny said.

Penny found some comfort knowing her daughter and her friends could keep an eye on Brian in Florida. But that didn't stop her from worrying. "I used to cry that if I send him away, he will die," Penny said. "Everyone told me I had no choice."

She said Brian completed detox at a hospital in Fort Lauderdale, but it took a while to find a bed in a sober home. The first one was in Boynton Beach, but Jessica said she found out the manager of the house was using drugs.

"It just broke my heart that that's how he was introduced to recovery," Jessica said. "Any place he was trying to get into, they weren't good places. It was like he never really had a chance."

Eventually, she said, she helped him get into an effective sober-living facility in Pompano Beach.

A week before he died, Brian sounded upbeat in a phone call with his parents. He was talking about the future, Penny said.

Four days later, on June 12, he was kicked out of the Pompano sober home because he failed a drug test. He told his mother he only took "a couple of Xanax." He said he wanted to come home to South Carolina.

— Jessica Grieb

Penny responded with tough love, telling him to stay in Florida. "I told him I wasn't going to talk to him and was going to make sure no one in the family would to talk to him until he went back into treatment."

He asked his sister if he could stay with her a day or two at her sober home in Fort Lauderdale. But Jessica said she had to refuse because she couldn't risk her brother being around other addicts who were trying to get clean.

With no place to go, he slept on the street one night and reached out to a friend from Pawleys Island who was living in a sober home in Delray Beach. The friend, Matt Jenkins, allowed Brian to stay with him a few days.

Meanwhile, Jessica made arrangements to get her brother into a long-term treatment program starting that Monday, June 15.

On Sunday morning, Brian called his mother again and asked to make a deal: He promised to go into treatment for two weeks if he could come home in July.

"I said, 'Brian, this isn't 'Let's Make a Deal.' You need to go into long-term treatment,"' Penny recalled.

"He told me I was aggravating him and he hung up as I tried to yell 'I love you' into the phone, like I knew it would be the last time I ever spoke to him."

One last high a day before treatment

Around 6:15 p.m. that day, Brian was invited to go out to dinner at a Mexican restaurant with Jenkins and his girlfriend, who lived together at New Freedom Halfway House in Delray Beach.

As they were piling into Jenkins' car, Brian changed his mind and decided to stay at the house. Around 7:50 p.m., Jenkins and his girlfriend returned to the house with food for Brian.

When they walked in, he wasn't around. They noticed the bathroom door was locked. They could hear water running. They banged on the door but got no response. Through the space beneath the door they could tell someone was lying on the floor.

"I kicked the door in and he was out cold on his back with his head resting against the wall. There was a needle on the ground and a spoon on the sink," Jenkins said in a sworn statement to sheriff's deputies.

Brian had no pulse and was not breathing. Jenkins tried to drag him into the shower, hoping cold water might somehow wake him. Other people in the house called 911 and tried to administer CPR until paramedics arrived at 7:56 p.m.

Paramedics worked on Brian for 30 minutes before taking him to Delray Beach Medical Center, records show. He was pronounced dead at 8:39 p.m.

The Medical Examiner's Office would list the cause of death as accidental "heroin toxicity."

While paramedics worked on Brian at the house, "We kept asking why they weren't hitting him with Narcan," Jenkins told deputies.

Brian was given two injections of Narcan, an overdose-reversal drug, according to medical records given to The Palm Beach Post by Penny. But those records don't clearly state exactly when her son received it.

She said a Fire Rescue incident report indicates the Narcan was administered at 9:03 p.m., but that was 24 minutes after he was pronounced dead at the hospital.

Asked by The Post to explain the reports, Fire Rescue Capt. Albert Borotto said he could not comment because of federal patient privacy laws.

"I think it being in his head (that) he was going to go to treatment tomorrow morning, and he wanted to get high one last time. That's what I'm assuming happened," a tearful Jenkins said in his statement.

Penny and Rich were driving back from the beach in South Carolina when they got a frantic call from Jessica. She told them she was on her way to Delray Medical Center after Jenkins told her Brian had overdosed. She promised to call back when she had an update.

Jessica said deputies refused to tell her anything for at least two hours. When a deputy finally confirmed Brian had died, she was too distraught to tell her parents. Gary Pierce, a family friend and recovering addict who was with Jessica at the hospital, called Penny and Rich with the news.

At first, it didn't register with Penny. As she stood in the kitchen of her home, she screamed into the phone at Pierce: "Tell them that he has insurance! They probably just aren't doing whatever they need to do because they don't know his has insurance!"

No, Pierce said to her, I'm so sorry. He's gone.

Recalling that conversation a year later, Penny choked back tears. "I seriously thought because he was an addict and died as an addict they just thought he was some homeless person and they weren't going to do whatever they had to do," she said.

It was just before midnight when a PBSO deputy called the Griebs in South Carolina with the official notification of their son's death. Penny scolded the deputy for waiting so long to call.

"It's like they treated it as though, 'Oh, well, just another drug addict off the street,' not realizing that's not who he was. He really wasn't," she said.

Brian's wallet returned with suspected heroin

Penny said her family received another slap from PBSO about six months later. When they returned home from a Christmas vacation in Sarasota, they found packages on their front porch.

"We thought, 'Oh, how nice. Christmas gifts,"' she said.

One box was from PBSO. She knew what it was. A deputy had called her in September to say Brian's case had been closed and they would be mailing her his personal effects.

"Why would you wait until a few days before Christmas to send it to the family? That is no common sense at all," she said.

But that wasn't the worst part.

When she opened the box, she found plastic evidence bags containing Brian's belt, some loose change, his wallet. She pulled out his driver's license and set his wallet aside.

Her father took the wallet and checked the tiny pockets and slots. He pulled out a small piece of folded paper. He opened it and found a yellow splotch, which Penny recognized as the same heroin she used to find in his room.

"They sent me back the one thing that killed my son," she said. "I was horrified. I could not believe it."

She called PBSO to complain. "I told them, 'He was treated as though he was just a number to you guys, as though he was not someone's son or someone's grandchild. He was just another drug addict."'

PBSO spokeswoman Teri Barbera confirmed that Sgt. Rick McAfee apologized to Penny.

"This was not done intentionally," Barbera said. "This was brought to the new management in our detective bureau's attention and they have advised that a new protocol has been put into place to make sure this doesn't happen again."

Barbera also emphasized that deputies, crime scene technicians and other personnel always do their best to treat grieving families with dignity and respect.

"We do care," she said. "We do know this is someone's loved one, someone's child. We don't want to give the impression we don't care. (Penny) is a grieving mother and we empathize with that wholeheartedly."

Blessed by a bright shining star in my life

A week after Brian died, more than 200 people attended his service in New Jersey. For the next 13 months, his ashes sat in a green box on a desk in his bedroom in South Carolina, until August when Penny and Rich drove back to New Jersey and buried them in a family plot.

Penny takes comfort in advice given to her by the family's priest, Father Ron Farrell at St. Mary, Our Lady of Ransom, Catholic Church in Georgetown, S.C.

"He said, 'Penny, the worst thing parents think that could happen to them is to lose their child. But it's not. It's not the worst thing. The worst thing is not to have had the child at all,"' she recalled.

"And he is right. I am truly blessed that I had such a bright beautiful shining star in my life. I really am. He was something else."

Brian's death has divided the Griebs' extended family and torn apart friendships. Some relatives and friends think Penny and Rich should have done more.

"I know in my heart that I did everything I could," she said, crying. "I tried my hardest to keep my son alive and unfortunately I failed."

She added, "The sad part is once you lose a child, not much else really hurts, even the awful things some might have to say about you or your family."

Penny and Rich said they have learned that the addict is responsible for his or her own recovery, no matter how much effort a parent makes.

— Penny Grieb

"Brian had an army of loved ones fighting on his behalf — family, grandparents and friends — and still in the end we lost," she said.

The guilt she carries over Brian's death has Penny constantly worrying about her daughter, Jessica. When Penny's phone rings, she often feels an initial jolt of anxiety — Please let Jess be OK.

Unlike Brian, Jessica volunteered to seek recovery. She's in her third or fourth stint now but she is working hard at her sobriety.

"Jessie is one of the lucky ones. Right now she is doing well," Penny said in an interview in July. "I say 'right now' because a lot of people have a problem with understanding addiction.

"We got a lot of backlash when Brian died. 'Oh, but you said he was doing good.' Jessie is doing very well right now. That, I know as a parent of an addict, can change tonight. I know I can get a phone call from someone saying. 'Jess is MIA."'

Her advice to other parents of children addicted to heroin: Dig in for a long fight and never give up hope.

"You are going to fight, cry, scream, pray. You are going to do all of those things over and over and over and over for years," she said, choking back tears.

"And then if you're lucky, if you're really, really lucky, you will have a recovering addict that for the rest of their life you are still sitting there with your fingers crossed and praying to God that they will survive."

Post staff writer Joe Capozzi and photographer Thomas Cordy traveled to South Carolina at Penny Grieb’s invitation to share her son’s story.

Staff researcher Melanie Mena contributed to this story.