By Barbara Marshall

Palm Beach Post staff writer

The day that changed everything was hot, like every other September day in South Florida.

Henry Martin was used to it. Like most West Palm Beach residents in 1955, his family didn't have air conditioning. Nor did Palm Beach High, his high school.

"We used fans," said Martin. "We didn't pay attention to the heat."

His school, built in Mediterranean Revival glory in 1908 on what was then the western edge of civilization, is Dreyfoos School of the Arts today. Before that, it was an integration compromise named Twin Lakes.

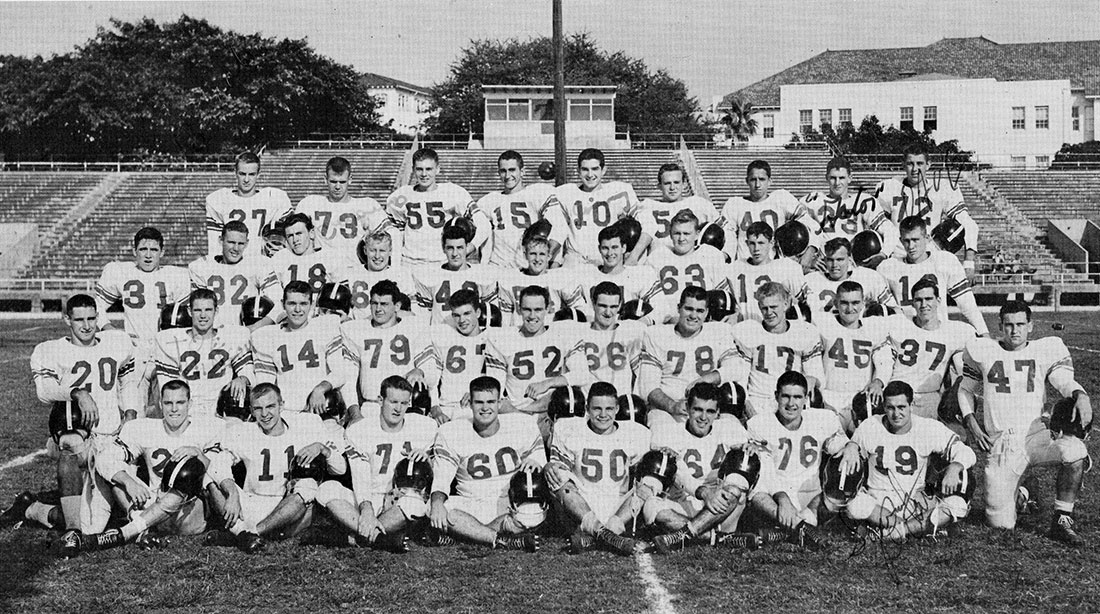

Palm Beach High School

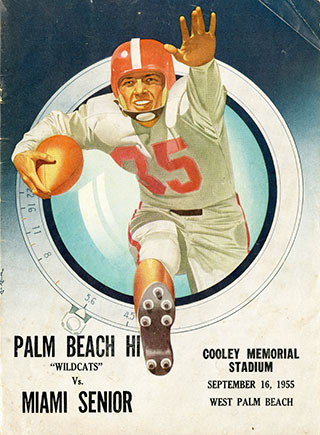

But before 1970, it was Palm Beach High, home of the Wildcats, where for one improbable season in 1955, Martin and his football teammates accomplished something no one thought possible.

For some of the students at the school that year, the echoes of what happened 60 years ago this month still reverberate through their lives.

He remembers all of it.

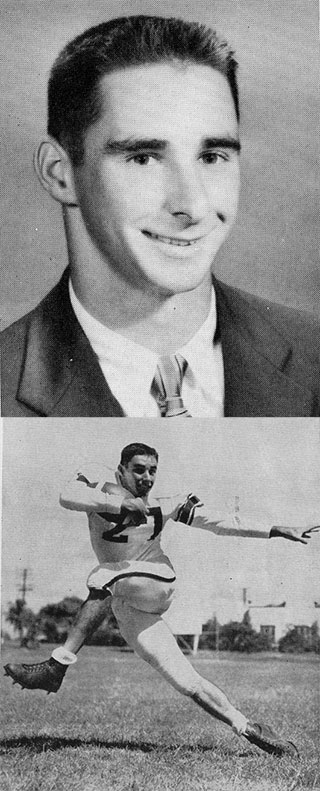

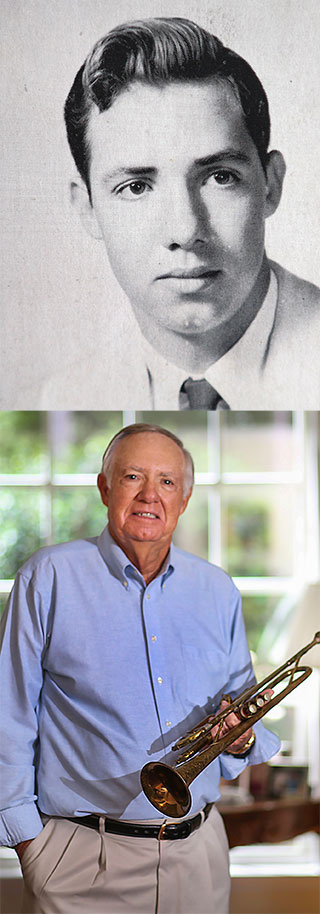

Henry Martin

Henry Martin

How he got so thirsty during football practice that he kept orange and lemons in his helmet to suck on during breaks. The thinking in those days was that drinking water during exercise caused cramps.

How the families at school all knew each other. How everyone came to football games under the Friday night lights. How important their high school was to their identity. How tiny his town was.

In 1955, West Palm Beach was a small segregated Southern city with two high schools for all the students from Jupiter to West Palm Beach: Roosevelt for the black kids; Palm Beach High for the whites.

"Anything west of the Seaboard tracks was still swamp," recalled Barkley Henderson, who played trumpet in the Palm Beach High band that year.

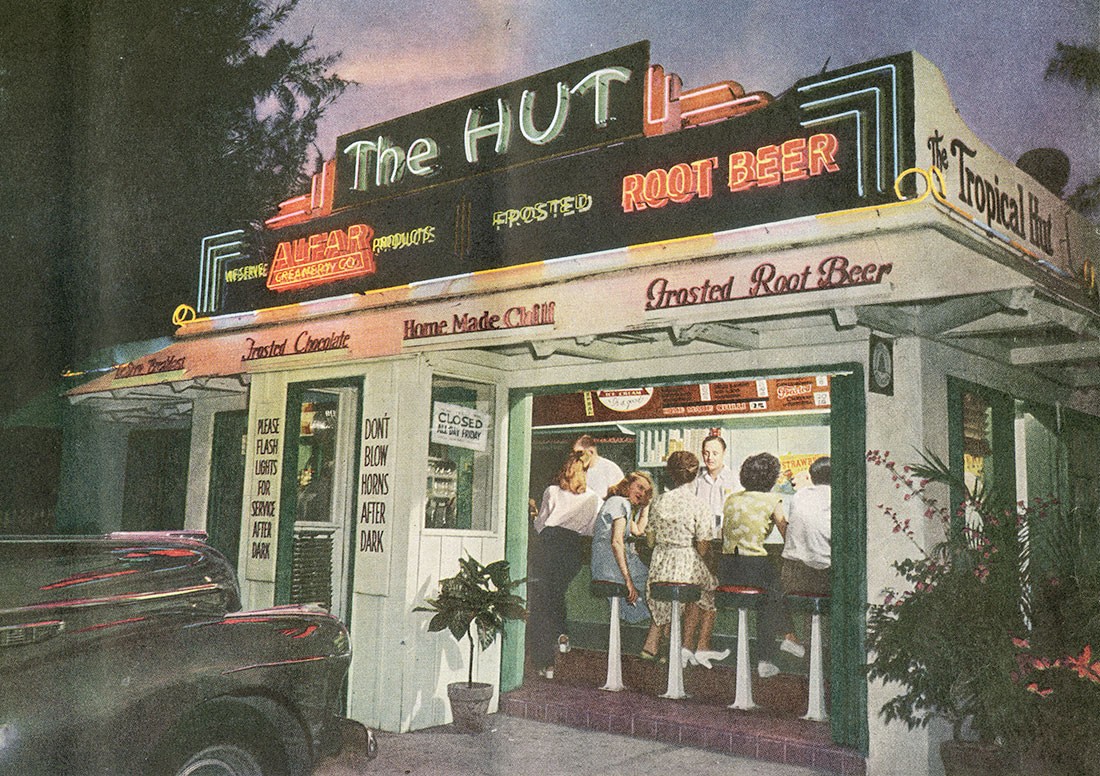

It was a world where girls with perms and circle skirts flirted with crew-cutted boys in chinos and penny loafers at The Campus Shop across from the school or at The Hut, a drive-in restaurant on Flagler Drive so iconic the Saturday Evening Post used it to illustrate post-war teenage culture.

"I lived at The Hut," said Martin, 77. "Everybody lived at The Hut."

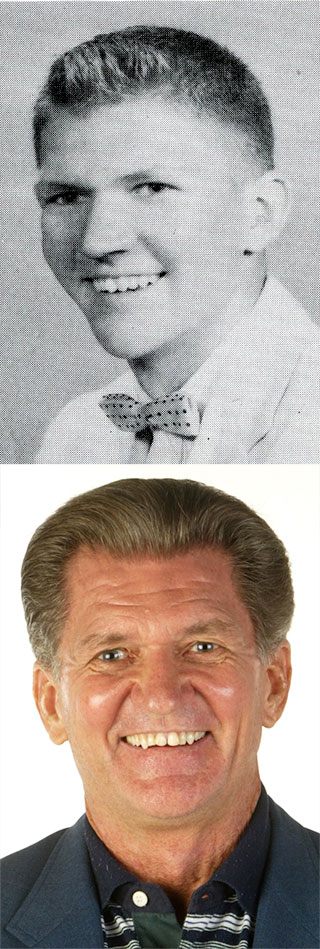

Barkley Henderson

Barkley Henderson

"I've always said they patterned 'Happy Days' after Palm Beach High in those days," said Henderson.

The Fifties some people yearn to return to? This was it, at least if you were white.

Even the hurricanes racing across the Caribbean stayed away that magic year.

"It was much smaller and in a way, much nicer," said Carole McCampbell Dorsey, a cheerleader.

"It was a golden time," remembered Henderson. "We were poor but didn't know it."

Few kids drank or smoked, said Martin. Sex? Not without a ring. Drugs? Only what doctors prescribed.

There's hardly an ethnic surname in the entire 1956 yearbook.

"We lived in our little cocoon," said Chuck Otterson, the school's sports editor who went on to a 40-year career with The Palm Beach Post.

Chuck Otterson

Chuck Otterson

Years after high school, he made a black friend who recalled not being allowed in downtown West Palm Beach after dark.

"If you were white, everything was one way….and if you weren't, it wasn't," Otterson said.

Football was everything: your school's reputation, a ticket to college for some, entertainment for the entire city.

Florida was so small in 1955 that the state's few large high schools had to travel across the state every fall to find schools of equal size to play.

The Palm Beach Wildcats took on schools in Jacksonville, Tampa, Orlando and Daytona Beach. They also played the most feared high school team in the state: the nationally-ranked Miami Senior High Stingarees.

Only four state teams had ever beaten Miami. By the mid-'50s, the school hadn't lost a game in years. To rustle up suitable competition, Miami started playing powerhouse teams in other states.

Palm Beach High had a new coach that year: Leonard Brown, a former quarterback at Missouri.

His first test would be Palm Beach's opening season game at home, against the ferocious Miami High machine.

"Playing Miami was like playing the University of Florida," said Henderson.

Martin, who played halfback and full back, and his teammates practiced extra hard that week in the swampy heat.

Brenda McCampbell Bailey, one of two McCampbell cousins who were cheerleaders, remembers dreading the sweaty night ahead.

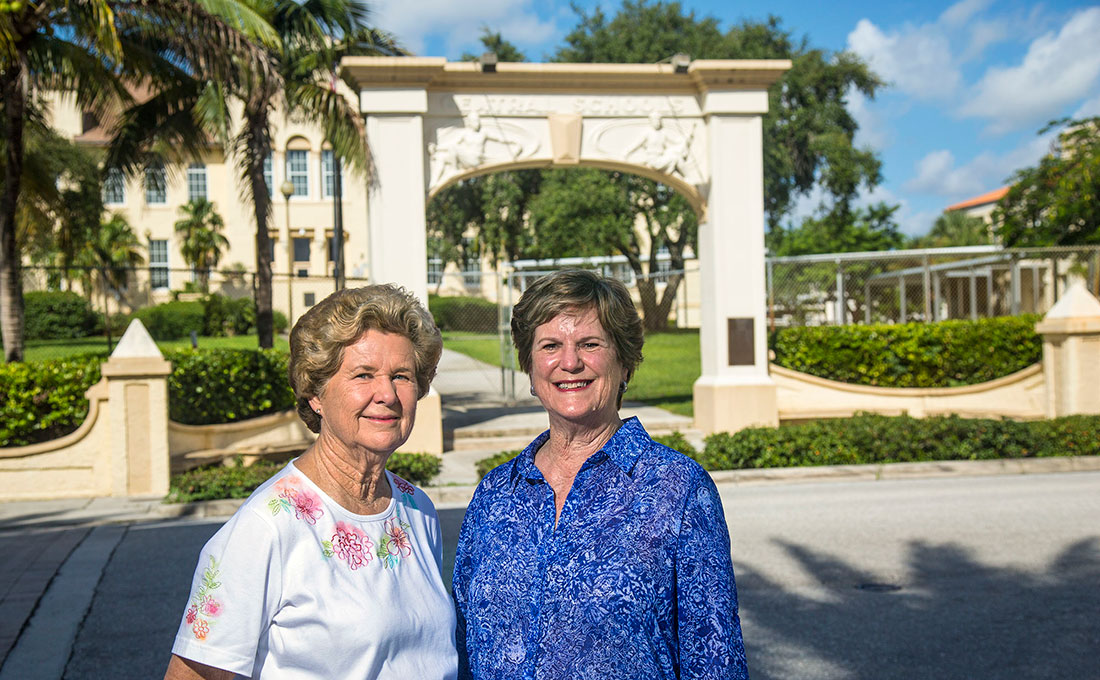

Brenda McCampbell Bailey (front row, left) Carole McCampbell Dorsey (front row, right)

Carol McCampbell Dorsey, left, and Brenda McCampbell Bailey (Lannis Waters / The Palm Beach Post)

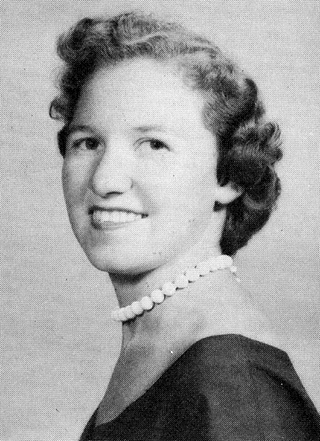

Shirley Greene Brown

Shirley Greene Brown

"We wore those long corduroy skirts, and big white sweaters with blouses underneath," she said. "We were so hot. Those nights were torture."

"Everyone was so certain we were going to lose," said Shirley Greene Brown, a senior who worked on the school's newspaper.

For most of us, high school is our last shared cultural experience before we begin to self-sort into ever-narrower categories.

Blue collar. College graduate. Member of the military. Liberal. Stay-at-home mom.

Yet what began September 16, 1955 created a bond that has persisted among these classmates for six decades.

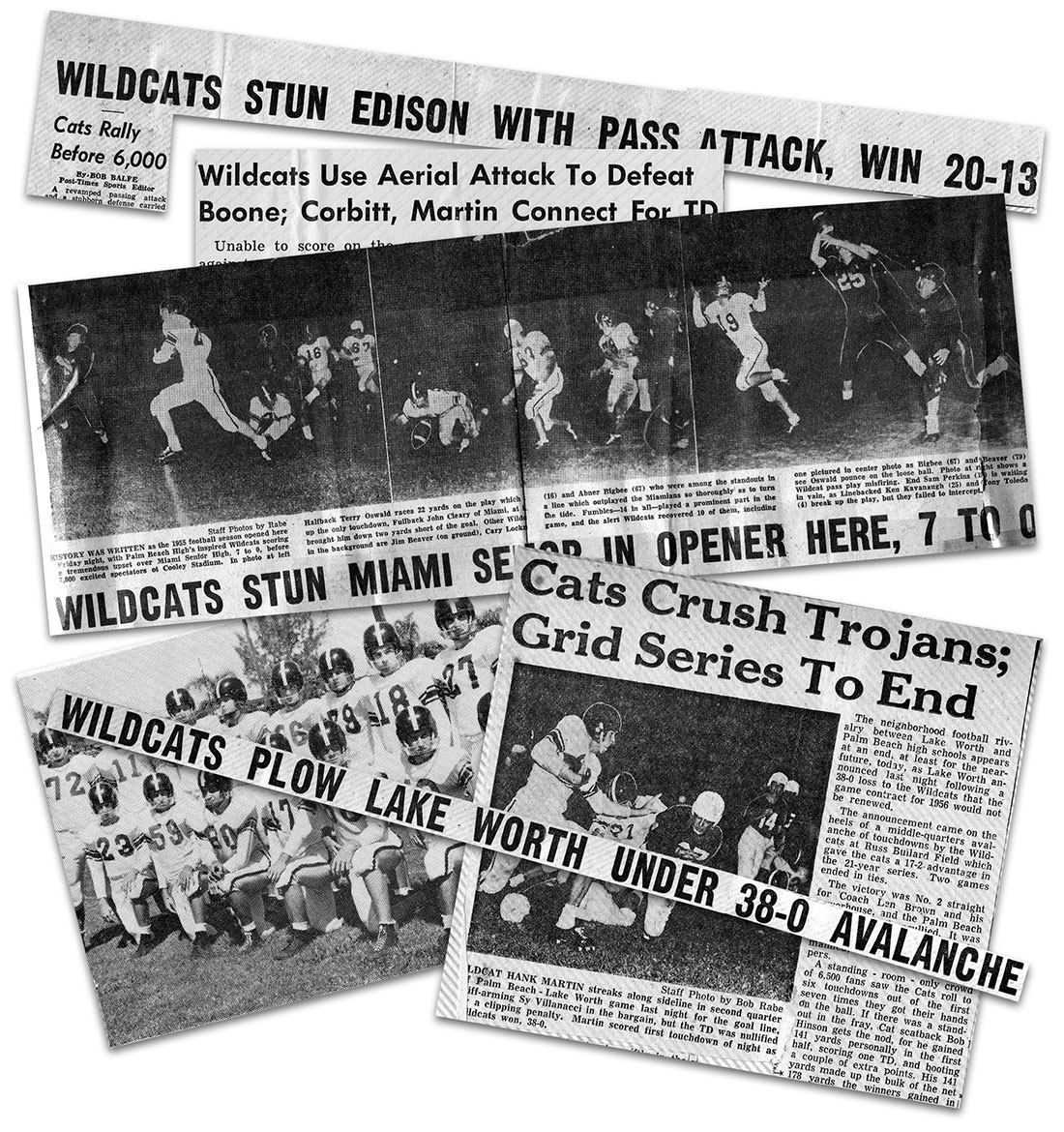

That night, 7,000 people crowded into Cooley Stadium on the school's west side. Newspaper sportswriters came from Miami to cover the game.

The Stingarees (another name for stingrays) showed up cocky, not bothering to bring their complete uniforms, remembers Martin. A track as well as a football star, Martin was known as the fastest man in the state, who ran the 100-yard dash at 9.6 seconds when the world record was 9.3.

"They came up here with the idea that they were gonna blow us away," he said. "But that's not what happened."

At 3:15 into the game, the Wildcats recovered a fumble and made the only score of the game. Palm Beach went on to recover 10 of the game's 14 fumbles, blocking an incredulous Miami from the end zone.

As the fourth quarter ended with a score of 7-0, pandemonium erupted.

"It was unimaginable for Palm Beach High School to beat Miami High. We just went absolutely crazy," remembered senior Jimmy Williams, who was in the west bleachers that night.

"History was written…" "A tremendous upset…," the sportswriters wrote.

"No one could believe we pulled it off. It was Fourth of July and a few other holidays wrapped into one, " said Henderson.

Says Williams, "We're still bragging about it."

After the day that changed everything, the football players became hometown heroes.

Palm Beach had discovered that Miami's technique of carrying the ball in two arms, centered in front of the body, was easy to thwart by pulling on one arm and spilling the ball loose, according to a front page story in the next morning's Palm Beach Post.

— Henry Martin,

Palm Beach High School Class of 1956

What happens when you or the people you're closely associated with do something unexpectedly wonderful at a young age?

Psychologists say events that occur in adolescence are among the most vivid and meaningful in life because teenagers are in the process of forming an identity.

After the day that changed everything, the Palm Beach High class of 1955/56 were forever identified as winners.

"The win lifted everybody up for the whole year," said Greene Brown. "The feeling was, ‘if we beat them, we can do anything.' We bonded in a special way after that."

"No question, there was a collateral effect that rubbed off on us," said Otterson. "You could go off to Gainesville and people knew Palm Beach High. It was something you took with you."

Yet, it wasn't a perfect season for Palm Beach High. They lost to Tampa Hillsborough and battled to a scoreless tie with Jacksonville's Lee High School.

But they went on to beat Miami Edison, another big Miami team, as well as two Orlando teams, in addition to Lakeland and Daytona Beach. Their last game was played in the Brahma Bowl near Orlando, where they beat Auburndale, giving the team a 8-1-1 record.

A photo taken that night shows Martin and two players hoisting Coach Brown on their shoulders.

Henry Martin (far right)

Later that school year, Palm Beach High was named the state's third best football team. Seven players were named to state all-star teams, including Martin.

Football scholarships followed as players were recruited by University of Florida, Florida State University, Notre Dame, Auburn and the University of Miami.

"Some players said the season changed their whole life because they wouldn't have been able to go to college without a scholarship," said Greene Brown.

Martin played at UM for two years until injuries ended his playing days. He joined the Navy, then worked as a supervisor at Western Electric, which was absorbed into AT&T. He retired 20 years ago but delivers cars for a rental company to have something to do.

Henry Martin (Lannis Waters / The Palm Beach Post)

He lives in Palm Beach Gardens, but on a warm September afternoon he's sitting among 60-year-old yearbooks and scrapbooks at his sister's kitchen table in West Palm Beach. It's the same El Cid property on which they grew up, although her house is new.

There he is in the 1956 Palm Beach High yearbook, honored as Most Athletic.

And he remembers.

"All my life, when things were tough, I thought, ‘I did that once, I can do it again.' It gave me a certain confidence, maybe I inspired respect. And it all goes back to when I was in school," Martin said.

The day that changed everything created a glue that stuck.

"It had an effect we didn't realize for years," said Otterson. "The turnout for our class reunions has always been unbelievable. Other classes have 30 people turn out, we get these terrific turnouts with hundreds of people coming from California, Colorado, Hawaii."

"We know each other's children," said McCampbell Bailey.

When members of the class run into each other, "It's like there's been no years in between," said Henderson.

"Even this many years later, we pick up our conversations from where we were the last time," said Greene Brown.

Maybe that's the real reward for that long ago championship season.