February 19, 1945.

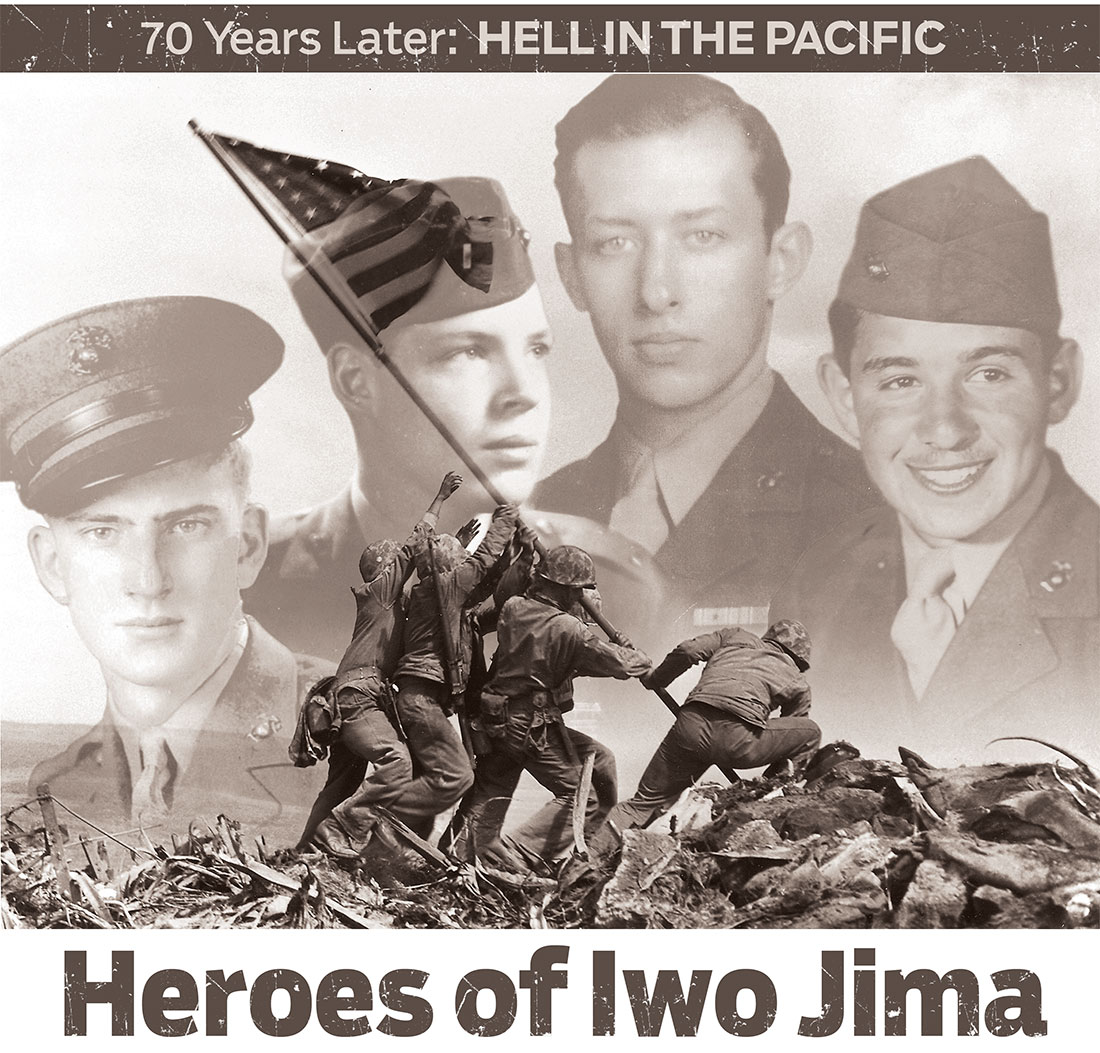

It was the beginning of one of the bloodiest battles of World War II – the Battle of Iwo Jima. Now, on the 70th anniversary, here are profiles of four Palm Beach County men who were there – and their memories of fallen comrades and the terrible carnage they saw and suffered through.

By Staci Sturrock

Palm Beach Post Staff Writer

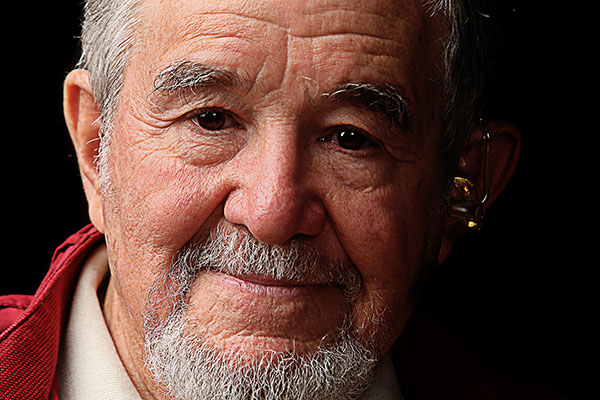

Joseph Dryer Jr., at his home in Palm Beach, in 2013. "It was the biggest and worst battle the Marine Corps ever had," says Dryer, who landed on Iwo Jima with the Fifth Marine Division on the first day of fighting and remained until he was shot March 17. "We lost a tremendous number of people," he said. (Gary Coronado/The Palm Beach Post)

"It was a much tougher battle than most"

JOSEPH DRYER JR.Palm Beach

When he landed on Iwo Jima 70 years ago this week, Joseph Dryer Jr. was a skinny, 23-year-old Marine lieutenant armed with a curious mind, a taste for adventure and a preternaturally sunny outlook. For 26 days, he fought and ferreted out a desperately recalcitrant enemy, dodging death repeatedly while, as he put it, American "troops were killed like flies."

Joseph Dryer Jr.

Joseph Dryer Jr.

Then, on St. Patrick's Day, fate squared off with Dryer. From 40 yards to his right, a Japanese sniper made the perfect shot.

"The bullet, a hollow point dum-dum ... should have gone through my heart, mushroomed and taken out my whole left side," Dryer wrote to his parents weeks later. "Instead, it hit my dog tags, cut off the bottom of my locker box keys, driving everything inside, went straight to the center of my chest, did a right-angle turn just as it reached the heart, and blew a huge hole in the center of my chest -- big enough to put your fist inside and see the heart beating."

His men called for a stretcher and a corpsman, who ripped apart what remained of Dryer's shirt, sprinkled sulfa powder on what had been his chest and injected him with morphine. The bumpy Jeep ride to the field hospital took 25 minutes. Novocain dulled the pain of a four-hour operation, but Dryer remained conscious while surgeons dug out a Milky Way of shrapnel.

Five more surgeries followed. Nine months of hospitalization. Last rites. "Several times they were going to give him up for dead," says Nancy, his wife of 57 years. "He had been told that if he ever could walk, he would be paralyzed on one side, but of course none of that happened. It was very miraculous that he was able to recover. But he's got a lot of willpower, and I guess he decided it wasn't his time yet."

Far from it. Dryer has lived a life worthy of an Ernest Hemingway novel -- it even features Hemingway, who attended Dryer's wedding.

"When you're young, the world is your oyster, and you can go anyplace," says Dryer, who farmed (and fled revolutions) in foreign countries, hosted heads of state and future princesses in his historic Palm Beach home, and developed hotels for KLM and Howard Johnson in Amsterdam and Jakarta.

In his cozy den, whose walls are decorated with antique rifles and a jaguar skin he purchased in Ecuador, Dryer pages through a crumbling scrapbook of photos he and his battalion photographer shot during World War II.

Amphibious training in California, liberty in Hawaii. So many snapshots of men in their prime, some of them with nicknames like Tex, Frenchie and Peepsight.

Dryer, who served with the Fifth Marine Division, pauses on one page. "These are my company officers. Most of them were killed. This was my colonel, whose chest was completely blown out.

"And this is on the way to Iwo Jima. Here's a model of the island and what our objectives were. Now these are actually going ashore for Iwo. This is on the way, and you can see the mountain in the background. It was very exciting. It was a thrill. An absolutely beautiful day."

Dryer turns another page, and suddenly the photos are splattered with inky black spots as images of smoke and shellfire and flak burst across the pages. But Dryer downplays the danger he faced on the island of black sand. "The Marine Corps had very, very good training, and we felt very competent about ourselves, and I don't think many people had delusions about what storming a beach would be about."

In his bedroom hangs a small collection of Iwo Jima posters and photos, one of a corpse-strewn battlefield. "That's me and another lieutenant with our two heads together in the center. That's our command post," he says. "When you're with people being shot left and right, and artillery and mortars are coming down on top of you, it was just exciting. We were trying to stay alive."

In the center of this 1945 combat photo, Lt. Joseph Dryer Jr. takes cover in a foxhole with a fellow Marine at the base of Iwo Jima’s Mount Suribachi. Dryer is the on the left. (Photo Courtesy Joe Dryer)

Dryer's post-war life would continue to be defined by episodes of action, adventure and occasional danger. In 1947, two years after Iwo Jima, he was one of 12 combat officers selected by the Marine Corps to create a plan to destroy the center of Russia's steel industry.

One day in Havana, Dryer recognized Ernest Hemingway sitting in the corner of a bar. "I went up and introduced myself, telling him that I had several of his rifles and shotguns given to me in 1943 by his eldest son, Jack, who was my best friend at Dartmouth."

Hemingway took Dryer under his wing and treated him like a member of the family. "He was wonderful," Dryer says. "All the time we spent with him -- days and nights and an awful lot of martinis -- I never heard him use a foul word or be as nasty as I've read about him in books.

"He was very comfortable to be with, a good conversationalist, easy. Anything you were interested in, he would get interested in. If you were interested in roses, he'd talk to you all about roses until he knew what you knew."

When Dryer married the Cuba-born Nancy Herrera in Havana in 1956, Ernest Hemingway and his wife, Mary, served as testigos (witnesses). "Mary said, 'Joe, Papa got all dressed up for you, and it's the first time he's worn a suit in years,'" Dryer said.

The Dryers' three sons were born in Cuba, and the family remained there 18 months after Fidel Castro came to power in 1959.

"Then one morning in 1961, the secret police came and took our house apart," Dryer says. "We decided it was time to leave."

The Dryers moved to Palm Beach because of its proximity to the Caribbean, its quality of life and its good schools, and they purchased a 1925 Marion Syms Wyeth house whose painted ceilings, tile floors and iron gates reminded them of the Cuba they loved.

Dryer has received some late-in-life recognition for his wartime service. A few years ago, the Dryers attended the annual Marine Corps Ball in Boca Raton. When he was introduced as the oldest Marine in attendance and a survivor of Iwo Jima, 600 guests stood and applauded.

"It was such an emotional moment, Nancy and I had tears running down our faces," Dryer says. "But what we (Marines) did was what we trained for. It didn't seem to be anything special. It was just a much tougher battle than most."

Palm Beach's Don Mates in 2010. Mates, a Marine veteran who received the Purple Heart and other honors for his service, has said that, if asked to go back to Iwo Jima and fight again, he would. But his son? "Absolutely not." (Damon Higgins/The Palm Beach Post)

"I don't want them forgotten"

DONALD MATESPalm Beach

Donald Mates of Palm Beach is a Marine vet who saw limited action on Guam before suffering severe wounds on Iwo Jima.

"You turn on the History Channel, you turn on the Discovery Channel, you turn on The Learning Channel, you turn on the Military Channel, and the first thing you're going to see is the 101st Airborne," the division that served in Europe and was popularized in Band of Brothers, says Mates. "The next thing you're going to see is Patton. And then on down the line, if they've got time, they'll throw in a picture of Iwo Jima."

Donald Mates

Donald Mates

Mates understands why D-Day and Dachau might attract more attention from documentary makers and feature film directors -- "You had crazy Hitler, you had the problem with him knocking off all the Jews and just unheard-of things."

But he says the fighting in the Pacific "was a lot tougher than Europe."

Something of a celebrity in veterans circles, Donald Mates has amassed several awards for his military service: the Purple Heart, Marine Combat Ribbon, Presidential Unit Citation, American Defense Medal, among others. A few years ago, a national foundation honored him at its annual Night of Heroes gala, citing his "valorous service at Iwo Jima where he suffered wounds which remind him daily of that brutal experience."

Collectors regularly seek his autograph, and "every time I go to speak, I spend half my time there being filmed. Everybody's a documentary maker now, and they're all trying to jump on the wagon."

Mates does have a particularly horrific story. As part of a reconnaissance company ("just this side of a guarantee that you'll get wounded"), Mates and seven others in the 3rd Marine Division volunteered for a nighttime patrol to find where the Japanese were launching deadly spigot mortars from.

Their observation post, a series of four foxholes, was roughly 250 feet ahead of the front lines, and at midnight, they were overrun by the Japanese, wielding rifles, bayonets, hand grenades and mines strapped to their bodies. The battle continued for the next five hours.

Machine-gun fire fractured Mates' foot, and a hand grenade went off between his legs, breaking both and causing considerable tissue damage.

Gangrene developed in his left leg, but Mates was allergic to the penicillin he was given and fell into a 10-day coma.

He spent the next 18 months in naval hospitals and, over the course of 30 years, underwent several operations to remove shrapnel and strengthen his limbs so he'd no longer need leg braces.

Iwo's volcanic ash continues to occasionally rise to the surface of Mates' skin, a reminder of what he survived. But he fears that the war is fading from our collective memory, that Iwo "is really just a footnote in history. The only people who come to hear me speak are old widows, children, grandchildren, historians and there's a whole crew of history buffs."

If he could speak to all Americans, what would he want them to know about the war in the Pacific?

He begins to cry but quickly composes himself, reaching for a folder on his coffee table -- "Let me show you something."

He flips through several pages until he finds a printout from the Chester County (Pa.) Hall of Heroes Web site, featuring a portrait of a sad-faced young man born in 1920.

"Here. Warren Garret. He was on patrol with me. ... Warren Garret, he was bayoneted to death. He had a 3-year-old daughter and a 1-year-old son. And he was the old man of the outfit. He was 24 years old."

Mates continues the grim roll call of his eight-man patrol and what happened to them one terrible night 65 years ago on an 8-square-mile Pacific island.

"Bill Reed. He was the corporal in charge of the patrol. He was shot.

"Joe McClosky. He just disappeared. Just disappeared. To this day, I don't know for a fact that they found his body.

"Warren Nietzel -- he was wounded horribly.

"Jimmy Trimble died the most violent death you could ever believe."

Here, his voice breaks again: "I just don't want them forgotten.

"They paid the ultimate."

Jack Cole, of Boca Raton, in 2010. He enlisted in 1944 because "in the fairy tales, the Marines were great fighters and were indestructible," he says. "And that's what I wanted to be." (Damon Higgins/The Palm Beach Post)

"Everybody did what was expected of them"

JACK COLEBoca Raton

Sometimes he could see the body. Sometimes he could smell the body. Sometimes he first heard the flies.

And when he located a fellow, fallen Marine on Iwo Jima, rifleman Jack Cole and another boy -- really, they were boys; Cole had turned 18 only a month earlier -- would lift them onto "stretchers so badly soiled they could no longer be used to transport wounded men," he says.

"You know what a Jackson Pollock painting looks like?"

Jack Cole.

Jack Cole.

They worked without gloves, face masks or body bags, loading the corpses onto a truck, stacking them in two layers.

Cole, a part-time Boca Raton resident, served 31 days on Iwo Jima -- that desolate speck of Pacific island, all black sand, craggy hills, sulfur pits, and caves, tunnels and pillboxes concealing the enemy.

This is how the retired manufacturing engineer now measures the results of that assault, which lasted 36 days in February and March of 1945:

"If you took their 21,000 dead, if you took the 6,000 or 7,000 dead that we had, if you laid them out on Iwo Jima ... you could make a carpet of bodies that would be almost 15 feet wide and about 3 miles long, and you could walk from one end of the island to the other on those bodies, without touching the soil.

"That's what happened there."

In the years since he helped collect bodies on Iwo Jima, Jack Cole has become an amateur historian, a student of war.

He feels that the Marines who landed on Iwo Jima were shortchanged by inadequate bombardment of the island prior to their landing and incomplete maps that didn't show, among other unwelcome surprises, the 16 miles of tunnels dug by the Japanese.

"Guys getting killed on the beach the first few days never saw the enemy. They never got off the beach."

He left Iwo without any wounds -- at least not the visible kind.

"You don't spend your days, all day, every day, with dead bodies, retching over them, without your thought process being changed in some respects."

But he quickly dismisses any thanks for his service.

"Everybody did what was expected of them," Cole says. "And if they survived, they were lucky."

Sam Saldano, of West Palm Beach, in 2010. After returning from the Pacific, Saldano says he "never spoke about (the war). It wasn't important anymore. But now you're getting old, and you have to recall." (Damon Higgins/The Palm Beach Post)

"I don't want to be considered a hero"

SAM SALDANOWest Palm Beach

Sam Saldano only reluctantly talks about his war experiences and doesn't advertise his three years of service in the Marines.

"It's something that's in here," he says, touching a closed fist to his chest. "I have hats and things, but I don't wear them. It's here. In the heart."

Part of the 4th Marine Division, Saldano landed on Iwo Jima at 9:05 a.m. Feb. 19, 1945, in the first hours of the invasion.

Sam Saldano.

Sam Saldano.

"Hit the beach and as I come up off the beach, the first thing I saw was a Japanese soldier who was in an oil barrel of some sort. Someone had flamed him, so he was cooking at the time," says the West Palm Beach resident.

"On the way up, a machine gun opened up on me. He followed me for awhile, so I went this way and that way and back that way, and I finally got around it. ... You ran a few feet and you dove into another hole."

At one point, the Marine sharing a hole with Saldano "gave me his weapon and said, 'I'll be right back.'

"He never came back."

Saldano narrowly escaped death his second day on Iwo when a shell exploded near him, killing a squad leader. Later, he was diving for cover "and a shell came up behind me and threw me, and rang my bell to an extent that at that point any voice I heard was like being underwater."

He spent the next week in an army hospital on Saipan, and later, six months in a Pearl Harbor hospital, a recalcitrant ear infection rendering him deaf at one point.

Saldano still feels somewhat guilty that he was unable to continue fighting alongside his comrades, but finally says: "I'm proud of what I did. I felt like I did what I could do.

"But I don't want to be thought of, or considered, a hero. I'm not. I was just there, one of the masses," says Saldano, who adds this: "Two minutes on that beach was too much."

The battle of Iwo Jima was immortalized in this famous photograph, by Joe Rosenthal, of a flag being raised on the top of Mount Suribachi by Marines and a Navy corpsman on Feb. 23, 1945.

When: Feb. 19-March 26, 1945

Where: Iwo Jima, part of the chain of Japan’s Volcano Islands, in the Pacific.

Casualties: More than 6,800 U.S. servicemen lost their lives on the Pacific island, and it was the only Marine battle where American casualties (about 26,000) outpaced Japanese casualties (roughly 22,000).