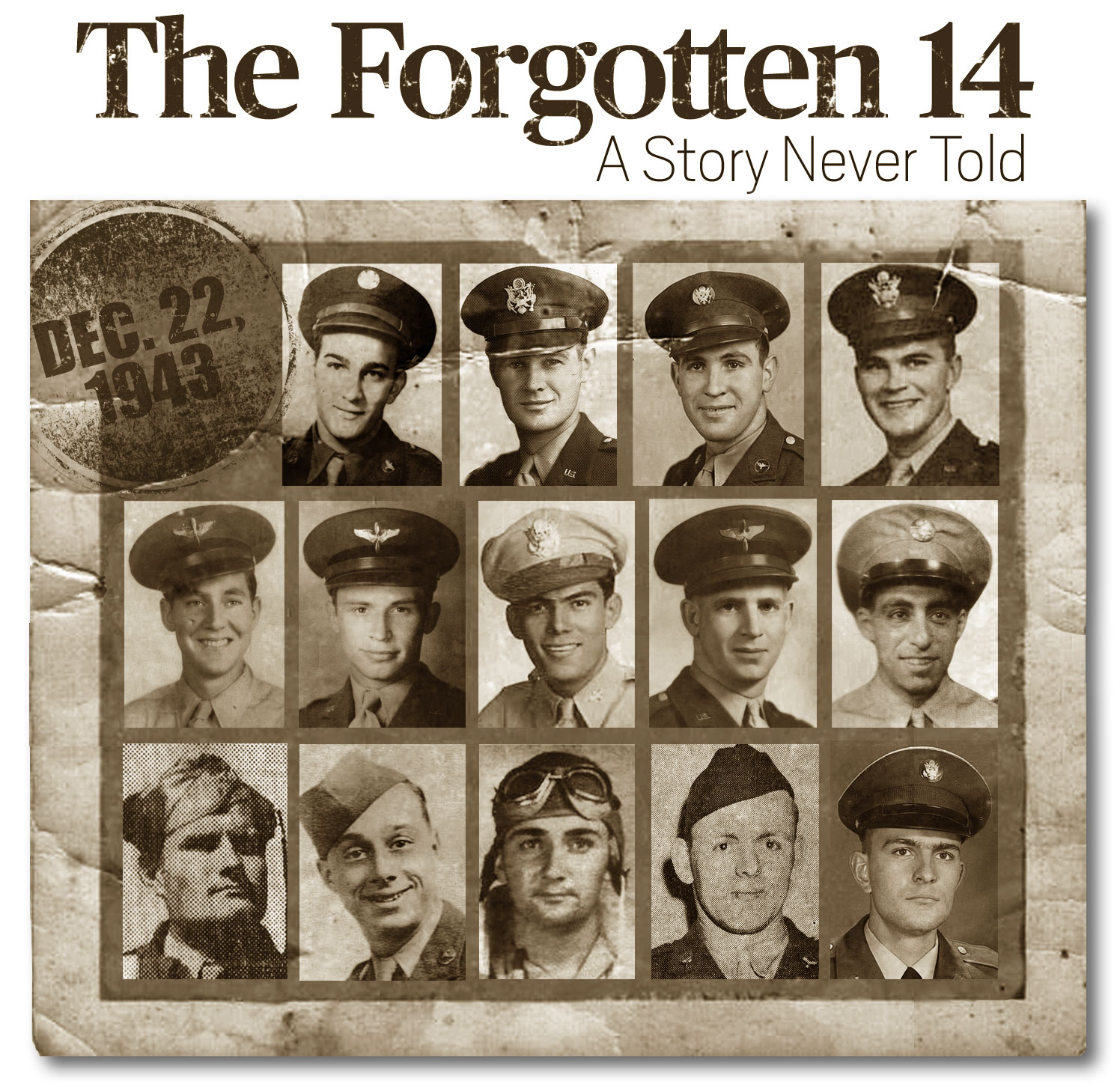

Three days before Christmas in 1943, two hours past midnight, 14 men climbed into an airplane and lifted into the dark sky over the slumbering hamlet of West Palm Beach. Their journey lasted but a few moments, and killed every one of them.

The crash is believed to represent the largest loss of life in a single incident at what is now Palm Beach International Airport. And you never heard of it.

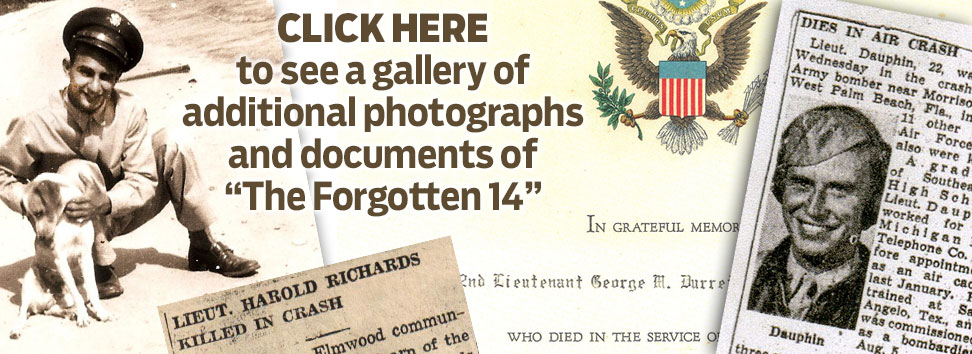

At the time, The Palm Beach Post reported it in a five-paragraph story on the front page, beneath a list of Christmas events. Then even briefer follow-up stories the next two days. Then nothing.

Eight days after the crash, New Year’s Day 1944 kicked off a year that would see the greatest invasion in world history and the beginning of the end of a great war. To all but those who loved them, the story of the 14 was quickly out of sight and out of mind.

Forgotten.

The Palm Beach Post

The Palm Beach Post

Dec. 23, 1943

By ELIOT KLEINBERG

Palm Beach Post staff writer

Monday is Memorial Day. We honor heroes, whether they died in glorious battle or in a sad accident. They are heroes, not because they died but because they knew they could die, and went anyway.

But there’s a special sadness in people dying in near anonymity.

The stories of the 14 had been small for two reasons. First, the government had directed America’s press to play down bad stories. It was hard enough to keep morale high in South Florida, where people could stand on the beach and watch black smoke from dozens of freighters sunk by U-Boats.

And, well, this crash wasn’t that big a deal. By the dozens, brave boys —and, yes, girls — were dying every day.

But of course, it was a big deal. It is a big deal.

The 14, whose deaths a reporter would stumble across seven decades later, were fathers and brothers and sons. Their faces beamed with hope and pride, in their neatly pressed dress uniforms, black and white studio portraits tinted with pastel hues. They dreamed the way we all do.

Bert, and Louis, and Doug, and Radamés, and the rest: A grateful nation cannot salute you enough.

You didn’t get the sendoff you deserved then.

You’re getting it now.

‘He wanted to fly’

West Palm Beach was no stranger to flyboys. Over the course of World War II, more than 45,000 fliers would train at Morrison Field, or stop there en route to the African and Italian campaigns and the D-Day invasion. Maintenance units did upkeep on the giant cargo planes that “flew the hump,” supplying Chinese insurgents battling the Japanese.

And the B-24 was no stranger to problems.

Louis Zorzi, who’d managed the base’s officer’s club, recalled in 1977 that more than one plane struggled to gain altitude.

“When they took off, they would be scraping the tops of the houses,” Zorzi said. He said many had to jettison cargo to stay in the air. More than one dropped into the ocean, survivors plucked out.

Later, the planes’ designs were modified. The B-24H was designed to carry 10 crew members, 10 .50-caliber guns and up to 6-½ tons of bombs. Depending on that weight, they could travel up to 3,700 miles.

Aircraft number 41-28632 had left Dec. 13 from San Francisco. It was greeted by “chamber of commerce weather” — highs in the 70s, lows in the 50s — when it arrived Dec. 20 at Morrison Field, Station 11 of the “Caribbean Wing” of the U.S. Army Air Corps, the forerunner to the Air Force.

Over the next two days, mechanics checked the engines, repaired a few minor leaks and declared the plane good to fly its next mission.

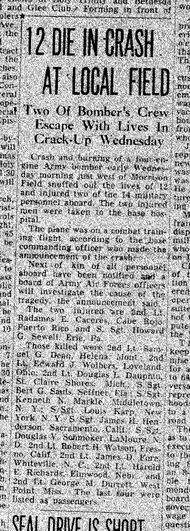

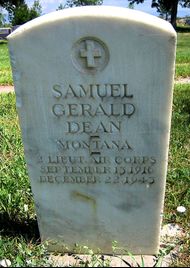

Samuel Gerald Dean, of Helena, Mont., was the pilot. And at 27, he was the oldest of the 14.

Born in North Dakota, he’d moved with his family to Montana. While he was an assistant manager at a Safeway grocery store in Miles City, he met Louise Amelia Svensson. They were married in Helena not long before he enlisted on Jan. 6, 1942, a month after Pearl Harbor. The next year, Louise was pregnant. Sam Jr. would be born Feb. 8, 1944.

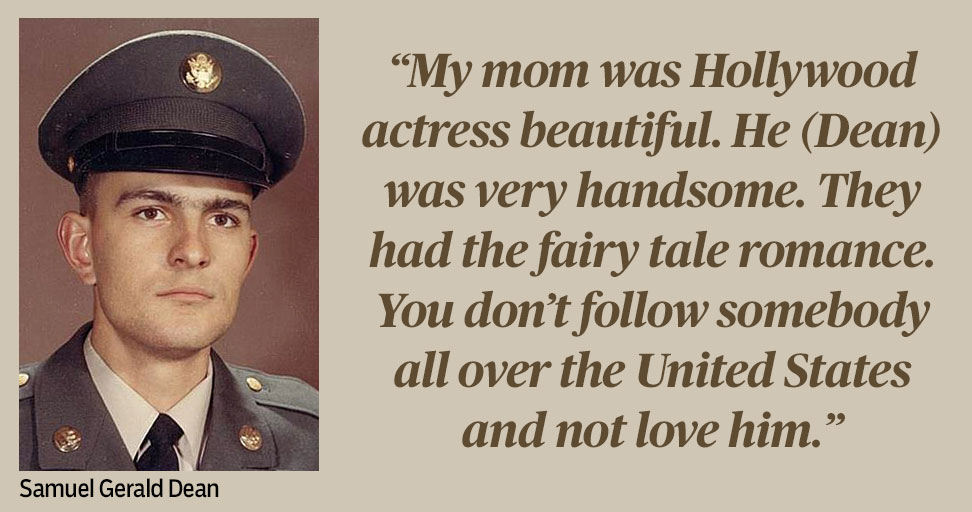

Louise “followed Sam all over the U.S. while he took all of his pilot training,” Sam Jr.’s half-brother, Bruce E. Nixon, said this month from Montana. “My mom was Hollywood actress beautiful. He (Dean) was very handsome. They had the fairy tale romance. You don’t follow somebody all over the United States and not love him.”

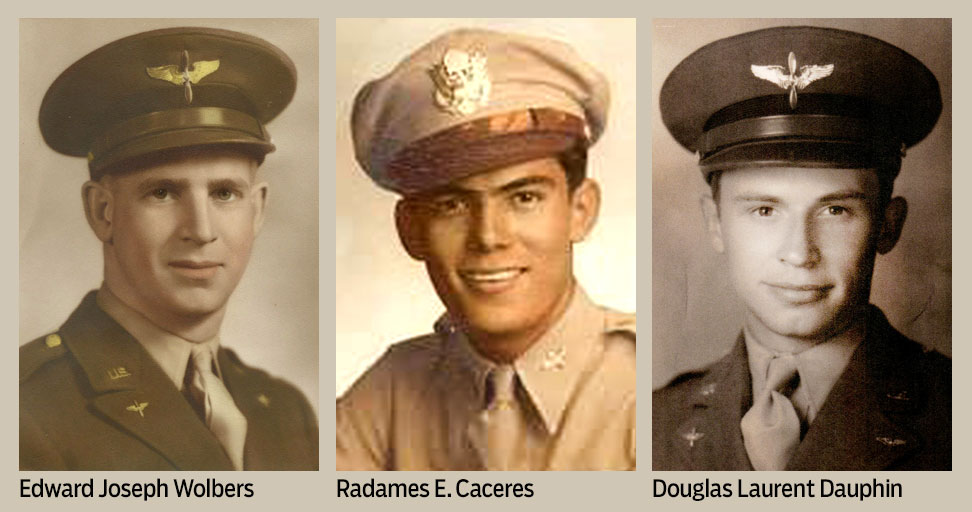

Dean’s co-pilot was Edward Joseph Wolbers of Loveland, Ohio. He was a Christmas baby. His 27th birthday was two days away. Single, and working as a clerk for a Cincinnati furniture firm, he’d crossed the Ohio River in July 1940 to Newport, Ky., to enlist.

Ed, the oldest of six siblings, “was a wonderful person. He was my son’s godfather,” sister-in-law Dorothy Wolbers, now 91, said from Loveland. “He’d do anything for you.”

The navigator was Radamés E. Cáceres, 21, from Cabo Rojo, Puerto Rico. Single, he’d enlisted in New York on Jan. 7, 1942, exactly one month after Pearl Harbor.

The bombardier was Douglas Laurent Dauphin, 22, of St. Claire Shores, Mich., near Detroit. Descended from French Canadians, he was one of six brothers. Five went into the military during the war, “and they all came back,” niece Margaret Dauphin said this month. “Except for Doug.”

Doug was a lineman for the Michigan Bell phone company. As a teenager, he sometimes frequented R.J.’s, a drive-in fast food joint across from a big amusement park. That’s where Henrietta Alexander worked as carhop.

“He came in one night with several of his buddies. She was their waitress,” daughter Debbie Simms said from Calabash, N.C. “She spilled a tray all over his lap. That was their initial meeting.”

The two “were childhood sweethearts. She was 16 or 17. He was a few months older,” Simms said. “I don’t know why he joined the service, other than he wanted to fly. They sent him down to the Army Air Corps.”

Doug enlisted in Detroit in July 1942. Henrietta visited her husband while he trained in Florida and Montana. The two were married in Pocatello, Idaho, in September 1943. They would be husband and wife for three months.

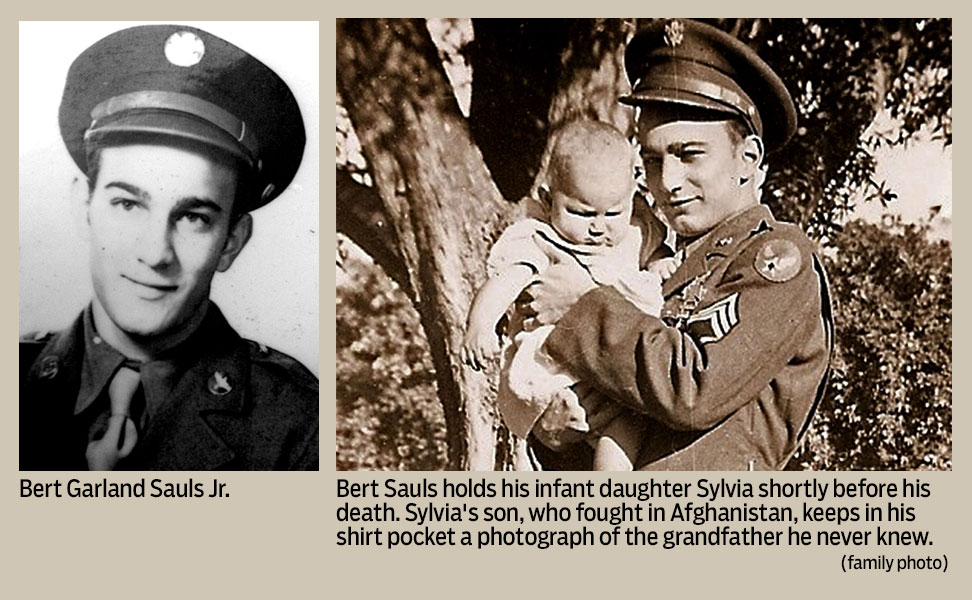

Master gunner Bert Garland Sauls Jr., 20, was the only Floridian. Born near Cleveland, he’d moved at age 3 to Mango, a little settlement near Seffner, east of Tampa. Sauls had enlisted Nov. 16, 1942, at Camp Blanding, north of Gainesville.

“My dad was a Christian and he wanted to fight for his country,” daughter Sylvia Diane Sauls Waugh said from Dunnellon, west of Ocala. She said Bert’s father wouldn’t sign the enlistment papers, but his mother did.

Bert Jr. had married Martha Waggoner of Bicknell, Ind., on May 28, 1942. Sylvia was born March 5, 1943. The night Bert died, his wife was carrying their second child, Linda Louise, who would be born two months later on Feb. 3, 1944.

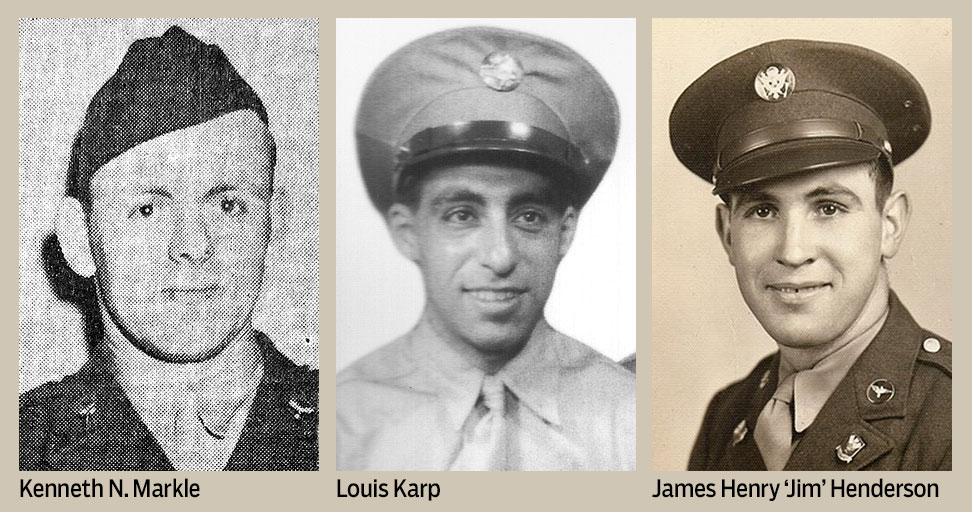

The radioman was Kenneth N. Markle, 25, of Middletown, N.Y. His mother was born in England. Single, he’d graduated from high school and on Nov. 8, 1942, had traveled 70 miles to New York City to enlist.

Artillery gunner Louis Karp, 25, had been a clerk in the Bronx when he answered the call and went down to enlist on Nov. 14, 1942. Still single, he was one of four brothers who would go to war.

A second artillery gunner, James Henry “Jim” Henderson, was 21. He was born in Texas, in the little town of Big Foot, southwest of San Antonio. His family had moved to California in the late 1920s, soon after Jim’s father died.

Jim, single, worked awhile as a civilian truck driver at Mather Field in Sacramento. Then he enlisted Oct. 16, 1942. The family already had lost a cousin, Pete. He died in Hawaii of non-combat injuries a month after the attack on Pearl Harbor.

“A lot of the cousins signed up right after that,” Star Filbert, the daughter of Jim’s niece, said this month from Sacramento.

Jim trained in Idaho, where he posted his last letter home on July 23, 1943.

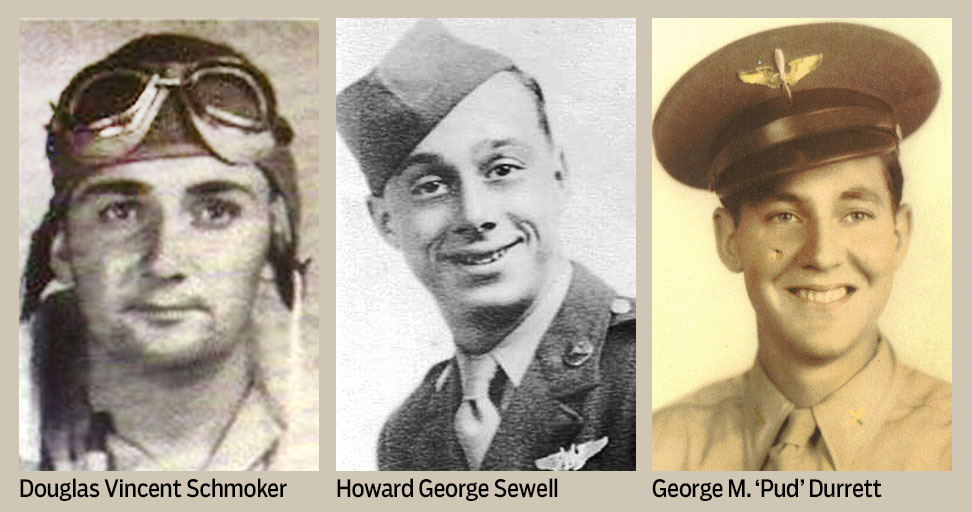

Artillery gunner Douglas Vincent Schmoker, 20, was from little LaMoure, N.D., about 100 miles southwest of Fargo. Single, he was the youngest of 12 children raised by a widow, and the only sibling killed in World War II. After two years in high school, he’d worked briefly at a defense airplane plant in California, then enlisted in the Army Air Corps in Los Angeles on Oct. 30, 1942.

The turret gunner, Howard George Sewell of Erie, Pa., was the baby of the group. He’d turned 19 two weeks earlier. Unmarried, but with a girlfriend, he’d gone into the military right out of Harbor Creek High, according to his only sibling, Elma Sewell Spacht, five years his junior. Their father had tested trains at the nearby General Electric plant, she said this month from Ripley, N.Y.

Four men were passengers, hitching a ride to someplace “secret.”

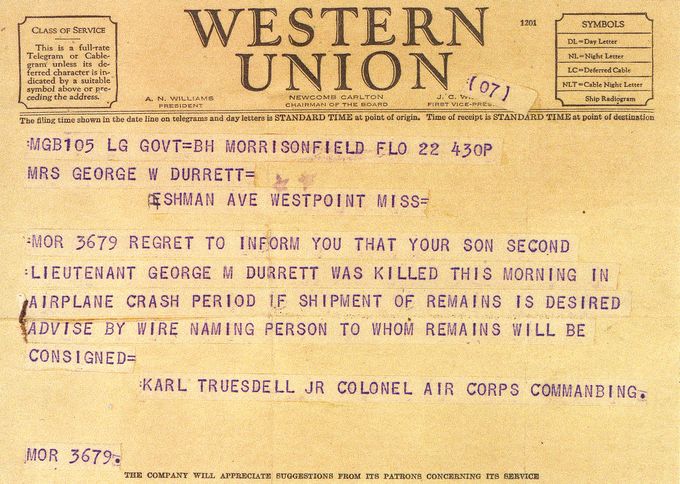

George M. “Pud” Durrett, three weeks shy of 23, was from West Point, Miss. He was one of four brothers who went to the military during the war, and the only one to die. He was an Eagle Scout, a high school graduate and worked as a clerk, niece Ruth Durrett Weeks said this month.

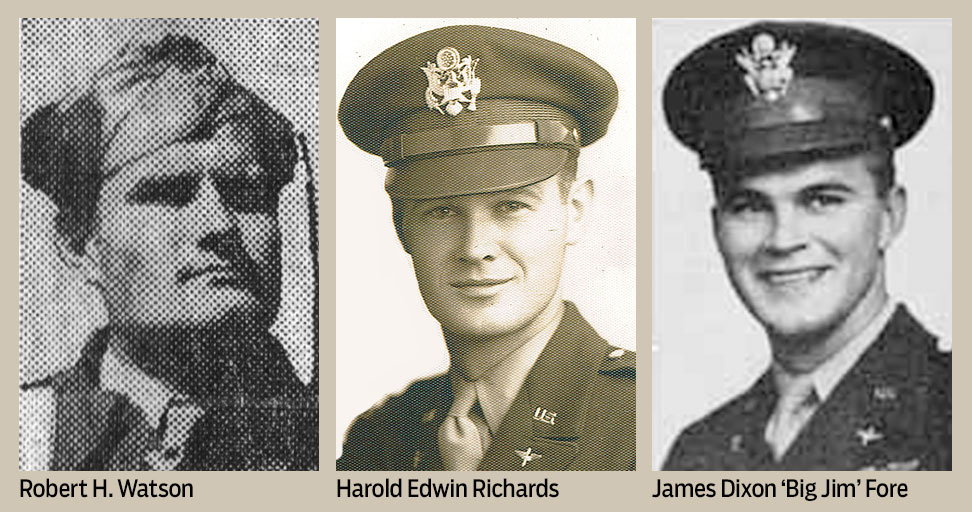

Robert H. Watson, 22, a Fresno, Calif., native, graduated from Roosevelt High and attended Fresno State College for one semester in 1939. He had a brother in the Navy.

Harold Edwin Richards, 25, from Elmwood, Neb., was a former National Guard member who had played for the Elmwood High football team and graduated in 1934, third in his class. He’d gone to work for Nabisco in Lincoln. He enlisted there Oct. 10, 1940. In December 1942, he was transferred to the Army Air Corps. He’d married Verna Faye Miller March 15.

The fourth passenger: James Dixon “Big Jim” Fore, 22, from Whiteville, N.C.

Fore might have been small town, but he was practically royalty.

The oldest of four, he was first in his family, and possibly the entire county, to graduate from the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, N.Y. Two days later, he married Theo Alcott Roberts. The two met while he was at West Point. Theo, a distant relative of Little Women author Louisa May Alcott, had attended the Woman’s College of the University of North Carolina, now UNC Greensboro. Seven months later, she would be a widow.

James “was very likeable,” sister Mary Fore Raines recalled this month. “He was very popular in high school and among his friends. Well thought of. He did well academically. He always admired the military. He liked that type of life. That discipline.”

At some point in his teens, he wrote his mother, “I look back and hate myself for every worry I have ever caused you. I guess that’s what God makes mothers for.”

Fore had gone to a military high school and then to State College (now N.C. State University) in Raleigh, and finally got his appointment to West Point.

“That was his dream,” Mary Fore Raines said. He turned down bids from both the Coast Guard Academy and the Naval Academy.

Fore's goal was to pilot a crew into combat. Now he was getting his chance. He was scheduled to hitch a ride to the war aboard a plane leaving West Palm Beach.

On Sunday night, Dec. 17, fellow passenger Durrett called his father from Memphis, saying he was en route from California to “another state.”

“Don’t worry about me,” he told his father. “I can take care of myself.”

‘The plane looked like confetti’

The Dec. 22 flight was described as non-combat, expected to take 10 hours. There was fuel for 14 hours. The destination was described later by base officials as “overseas” but listed in the crash report only as “secret.”

The weather was clear. Departure was set for 2 a.m.

Ed Wolbers, the co-pilot, who had 589 flying hours, signed the manifest and got a final clearance at 1 a.m. Earlier, he’d mailed his family a card bearing his photo and a drawing of a winter scene. It said only “Christmas Greetings” and was signed “Ed.”

It arrived after his death.

Bert Sauls’ family says he called home just before the flight left and told an aunt he was worried: “We’ll never make it. We’re overloaded.”

At 2 a.m., the B-24H came off the 7,000-foot northwest runway, the same one used today. A crash report later described the engines, load and takeoff as normal.

About three-fourths of a mile after it cleared the end of the runway, the plane struck the tops of three or four Australian pines. Parts of the engines later were found at the base of the trees.

The plane veered left and came down three miles from the runway. It briefly bounced off the ground, then crashed in a cow pasture that today would be north of Belvedere Road and halfway between Haverhill and Drexel roads.

Then, the full fuel tanks exploded into flames.

Braymer G. Hood, the base’s “airdrome officer,” raced to the scene but could not get all the way to the crash. He and two others, his driver and an MP, had to wade through swamp waters in the dark.

“Ammunition was exploding, flares were blowing up, and a fierce fire was in progress,” Hood said in his report to investigators. He said three men were found about 20 yards from the fire; one was still alive.

Also on the scene was Edwin F. Froehlich, a big local dairy operator, who owned an adjoining pasture and lived nearby. He had raced from his home to the crash.

In an October 2012 interview with the Historical Society of Palm Beach County, son Edwin Froehlich II recalled his father saying that “the plane looked like confetti all over.”

Edwin’s wife, Donna Jean, said a loud noise shook the entire home. She had just seen through the window “the operating lights of an airplane which was flying very low,” Milton W. Howard, an agent from Morrison Field, reported. “The plane … appeared to be burning slightly and suddenly became enveloped in a huge sheet of flame. It fell at once, and she heard an explosion.”

Sol Washington also had come to the crash and said he’d found a man alive and took him home. From there, the man was taken to the base hospital. That was the navigator: Radamés Cáceres.

It would be an hour and a half before things stopped exploding and firefighters could try to knock down the horrific blaze. Only then could the bodies be recovered from inside and around the plane.

Later, the only other survivor, Artillery Gunner Howard Sewell, was able to talk to Maj. John M. Tillman from his hospital bed. Tillman asked which engines had failed. None, said Sewell. “They were purring like kittens.”

Sewell “said that they were all sweating the pilot to pull the airplane up a little higher on take-off and then they hit something, and that after he hit something, it seemed as though they got in the air again, and then the airplane veered to the left and went on in.”

Tillman reported Sewell “was trying to infer, in my mind, that he resented anyone saying that the airplane was not functioning properly.” Tillman said Sewell “felt that the pilot did not get the airplane high enough, yet he didn’t care to actually make a statement that anyone in particular was to blame.”

A Dec. 24 post-crash statement would say that Dean, the pilot, had been “sober and in good physical and mental condition and thoroughly capable of performing his duties as a pilot.”

At 7:30 p.m. on Dec. 22, some 17 hours after the crash, Radamés Cáceres died. At 1:50 p.m. Dec. 23, some 35 hours after the crash, Howard Sewell died.

On Dec. 29, the crash report was complete. The conclusion: The plane “failed to attain sufficient attitude” to clear the trees. The reason: “unable to determine.”

“She knew. She knew.”

The Wolbers family didn’t have a phone. A neighbor who did came over to break the news. Ed Wolbers’ mother knew immediately from the look on the neighbor’s face. At the time, three brothers were in the military. She said, “Which one is it?”

It was her first born. Born on Christmas and killed near Christmas.

“After that,” nephew Ed Wolbers Jr. recalled, “it was never a big holiday for her.”

The elder Ed's brother Lawrence drove a Greyhound bus. His wife tracked him down in Indianapolis to tell him.

Back in Michigan, Doug Dauphin’s wife, Henrietta, living with her parents, heard a car door open and close outside. She looked out her window and saw men get out, “and she knew. She knew,” daughter Debbie Simms said this month.

A little later, Doug’s effects were returned, among them a watch he had bought his wife for Christmas. She hadn’t had time to get him something yet.

Henrietta was all of a month into a pregnancy and probably didn’t yet know it. Debbie would be born in August 1944. Henrietta would remarry.

In the little town of Mango, Bert Sauls’ mother had just returned from Christmas shopping. Two of Bert’s young sisters were decorating the tree.

There was a knock on the door. His mother and one of the girls were on the porch with the man for a long time. The other sister, Helene, went outside.

“My sister started crying and said, ‘Junior’s dead,’” Helene Sauls Greenwood recalled from the living room of her niece’s home in Dunnellon. Even at 8, she said, she could fathom that.

“We cried so loud that the neighbors heard us,” she said.

Bert’s father drove a truck delivering groceries up and down U.S. 19 between Tampa and Yankeetown. He’d been at the north end of his route when the telegram arrived at his home. At one stop, he picked up a newspaper and saw a headline that told him his son was dead.

“I don’t know how Daddy made that 100-mile trip back to Tampa,” Helene said. “I ran out to meet him, and he just walked right by me and collapsed when he got in the door.”

Bert’s wife, Martha, had recently returned to Florida after visiting with him in California. Now she was a young widow with a 9-month-old child and another on the way.

Later, Martha’s mother split with her husband and moved down from Indiana. The other grandparents also divorced. Then Martha’s mother married Bert’s father in 1945, on his daughter Sylvia’s fifth birthday.

A few years later, Sylvia and her sister Linda Louise became orphans. Martha died of cervical cancer in 1948. She was 24. The two girls were raised by their new blended grandparents.

“I had girlfriends that had fathers and I remember being jealous,” Linda Sauls White said. “Someone would say, ‘My daddy’s going to do things with me.’”

Louis Karp died on the first night of Hanukkah, and on the birthday of his mother Jennie.

She worked for a caterer in New York City. Officials from Morrison Field, not knowing she hadn’t yet received the iconic telegram, called her at work to ask where to ship her son’s body. That’s how she found out.

The day after the crash, brother Julius Karp flew into Morrison Field en route to deployment in Europe. From the air, he saw the charred wreckage of a B-24H. It would be months before he’d learn that that crash had killed his brother.

About six months later, Julius, was shot down over Germany. He would spend more than nine months as a prisoner-of-war. Early on in the war, he’d taken pliers and flattened out the “H” stamped on his dog tag — Hebrew — for fear of what the Germans would do. He told his captors he was Protestant.

Julius’ family presumed him dead.

“Most of those on his plane parachuted and were murdered when they landed,” Julius’ son, also Louis Karp, said this month from Boulder, Colo.

With Milton Karp not yet in the service, that left the fourth brother, Morris, stationed in Belgium and poised to enter the Battle of the Bulge.

Morris’ wife and mother both sat down and composed a letter to the president of the United States. Jennie Karp asked Franklin Roosevelt, “Would you please bring home my son?”

If this sounds familiar, it was the premise of the film Saving Private Ryan. And as in the movie, the military found Morris and got him a job Stateside. Many in his unit later would be killed, sister Edith Gale said from Farmers Branch, Texas, near Dallas.

The family of Jim Henderson hadn’t known he was planning to ship overseas, “so it was quite a shock” when a military official made that phone call, recalled Star Filbert, his niece’s daughter.

George Durrett’s family in Mississippi also didn’t even have a phone, and the military men had to call a neighbor to go next door.

In North Carolina, James Fore’s 11-year-old sister Mary was home sick. She’d missed the last day of school before Christmas.

“I remember that day vividly,” Mary Fore Raines, now 81, said this month. Her mother answered the phone but was hard of hearing and couldn’t understand the caller. She asked him to call back later when her husband, a rural mail carrier, was home.

James’ father did get home and got that call, from a chaplain.

“The grieving he did was very private,” Mary said. “I never saw him break down. But I know he did.”

In Erie, Pa., a telegram arrived for the parents of Howard Sewell. Later, 14-year-old Elma Sewell went with her parents to a funeral home. While she sat outside, her parents identified their son.

Pilot Sam Dean’s wife, Louise, had just been visiting him in Florida and had left Dec. 20. When she returned to Montana “is when she got the news,” stepson Bruce Nixon said. Dean’s hat and wallet, which somehow had survived the crash and fire, were sent to his widow.

‘Glory to them that die in this great cause’

Within days of the crash, accompanied by a military escort, Mizell-Simon Mortuary, 413 Hibiscus St. in West Palm Beach, began sending the bodies of The 14 on their journeys home. Cáceres, from Puerto Rico, would take a little longer. But 13 of the 14 would be on their way by that Saturday. Christmas Day. The birthday of Edward Wolbers.

Wolbers’ body arrived in Ohio on Christmas Eve, but the military escort slept with the casket at the Loveland train station, rather than force the family to cope with it on the holiday. Ed Wolbers is buried at Gate of Heaven Cemetery in Cincinnati.

“I mean, how many did we lose in that war, for crying out loud. It’s just another stat,” nephew Ed Wolbers said in the kitchen of his home in The Villages, near Ocala. “But he’s always been a point of pride for the family.”

Two weeks after Samuel Dean’s death, Louise Dean signed an application for an upright marble headstone for her husband. It would be shipped from Vermont via rail to Resurrection Cemetery in Helena, where he is buried. Louise had $1,000. She took her infant son and bought a 160-acre horse ranch in the Montana wilds. She’d stay there for six decades, dying at 92 in 2009.

On July 20, 1949, some 5½ years after the crash that killed his son, Juan Silvestre Cáceres applied for an upright flat granite headstone. It was shipped in August 1950 from Columbus, Miss., to the Cabo Rojo Cemetery in Mayaguez, where Radamés Cáceres is buried.

Doug Dauphin is buried at Mount Olivet Cemetery in Detroit, Bert Sauls at Myrtle Hill Memorial Park in Tampa, Louis Karp at Mount Lebanon Cemetery in Queens, Howard Sewell at Wintergreen Gorge Cemetery in Erie, and Ken Markle in the family plot at Walkill Cemetery in Phillipsburg, N.Y.

George Durrett is buried at Friendship Cemetery in Columbus, Miss.. His stone says, “Prepare to meet me in heaven.”

At graveside services for Jim Henderson at Sacramento Memorial Lawn Cemetery, an Army Air Corps band came from nearby Mather Field, where Jim had driven a truck before joining the military.

At the Catholic cemetery in LaMoure, Doug Schmoker’s pallbearers were six of his brothers. Former servicemen, veterans and legionnaires formed an honor escort. A squad of riflemen sent three volleys echoing over the North Dakota plains. Two buglers played taps. And, as per tradition, the American flag draping Schmoker’s coffin was folded in a military triangle. Chaplain Albert Ness presented it to his mother, on behalf of a grateful nation.

Robert Watson was returned to Fresno for funeral services under the direction of Sullivan Burns and Blair Funeral Home.

Services for Harold Richards were held Dec. 28 at the Methodist Episcopal Church in Elmwood, Neb. Officiating was Rev. H.A. Fintel, the man who’d performed the Richards’ wedding ceremony in March 1943, just eight months earlier. Richards is buried in Wabash Cemetery, Wabash, Neb. His stone reads, “Glory to them that die in this great cause.”

Jim Fore was featured in the July 1944 “Assembly,” the magazine of West Point graduates. He is buried at Whiteville Memorial Cemetery in North Carolina.

Bert Saul’s daughter Sylvia has a son, Steven Waugh, in the U.S. Army. He fought in Afghanistan. He carries in his left shirt pocket a photograph of the grandfather he never knew.

This month, Linda Sauls White was asked about her father, who died two months before she was born, whom she never knew. How would she like the nation to remember him?

She thought about it, then said simply, “with honor.”

Ken Markle left a grieving mother, as those men nearly always do. A woman who had to remove a blue star from her window and replace it with one of gold.

This small item appeared Dec. 22, 1948, in the Middletown, N.Y., newspaper:

“IN LOVING MEMORY of Kenny, Kenneth N. Markle. Army Air Corps, who left us so suddenly five years today. December 22nd, 1943. Some day, some time. We will understand. Mother.”

What’s now Palm Beach International Airport started in 1929 as a field with a windsock called Lightbown Municipal Airport. It later was named for Grace Morrison, secretary to architect Maurice Fatio. She’d championed the creation of a local airport.

Morrison Field was dedicated Dec. 19, 1936. Morrison was not there; she had been killed months earlier in a car crash. The airport was a military base during World War II and the Korean War. Returned to the county for good in 1961, it became home in 1966 to a five-building terminal four times the size of its predecessor. In 1988, a new $150 million terminal rose along Belvedere Road.

It’s believed there’s never been a fatal civilian commercial air crash at what’s now Palm Beach International Airport.

- The first commercial flight ever from Morrison Field, an Eastern Airlines flight with 11 people aboard that departed the day the field opened in 1936, crashed near Port Jervis, N.Y., en route to Newark, N.J., but remarkably, no one died.

- Eight died in two 1956 military crashes during the airport’s time as an Air Base during the Korean War. On Feb. 21, a Stratofreighter — a long-range heavy military cargo aircraft based on the B-29 bomber — crashed and exploded on approach, killing all five aboard. And on Aug. 21, a giant C-124 Globemaster transport plane slammed into a nursery 3 miles southeast of the base, killing three aboard; three others were hurt but walked away.

- On Sept. 12, 1980, a gambling junket flight to the Bahamas with 34 people aboard dropped into the ocean near Freeport. The plane and victims never have been found.

People, agencies that helped

Families and friends of the Forgotten 14

U.S. Air Force Historical Research Agency, Maxwell Air Force Base, Ala.

Debi Murray, archivist, Historical Society of Palm Beach County.

National Archives World War II enlistment records. U.S. Census, 1940. U.S. Military Academy.

Search sites: www.Familysearch.org, www.geneaology.com, www.ancestry.com, www.wikitree.com.

Newspapers: Fresno (Calif.) Bee, Sacramento Bee, Tampa Tribune, West Point (Miss.) Daily Times Leader, Missoula (Mont.) Missoulian; Lincoln (Neb.) Star, (Lincoln) Nebraska State Journal, Middletown (N.Y.) Times Herald, LaMoure (N.D.) Chronicle, Erie Dispatch-Herald, Erie Daily Times.

Public libraries of Fresno, Calif.; West Point, Miss.; Middletown, N.Y.; Erie, Pa.

American Legion Post 247, Elmwood, Neb.; Historical Society of Middletown and the Wallkill Precinct (N.Y.); Puerto Rican Hispanic Geneaological Society. Montana Historical Society. Carroll College, Helena, Mt.

Special thanks to staff writer Susan Salisbury, staff researchers Michelle Quigley and Melanie Mena, and staff photo editor Gwyn Surface.