There was no moon the night we went searching for the graves of murderers and the murdered.

We knew the damp earth of Woodlawn Cemetery in West Palm Beach hid century-old secrets. Photographer Lannis Waters and I were hoping to find them.

Here among the gnarled roots of brooding banyan trees lie the final resting places of some of Palm Beach County's oldest and most tragic stories.

We sought the graves of the murdering Postmistress who taught Sunday School, the empty graves of a couple swept from their beds one night, wrapped in weights and tossed into the ocean. The courageous pioneers who braved disease, insects and the summer infernos to wrest cities from swamp and beach jungle when South Florida was the country's last frontier.

Then, as we were photographing a headstone, two strange lights appeared.

Slowly, they moved closer. Twin ghostly orbs wavered in the humid air.

We were transfixed at the lights' inexorable approach. Had we disturbed the dead? Was this some unholy retribution for trespassing on souls' rest?

Then we were caught in lights so bright we couldn't see what was behind them. We heard a whirring sound and felt a chill, like death's cold breath. Then the voice, eerie in the cemetery's black stillness:

"Are you guys done yet? I gotta lock up for the night."

A city worker, anxious to go home, was calling from the rolled down window of his SUV.

So OK, nothing frightening happened during our night at the graveyard.

But there are scary, odd and sad tales lurking behind those stones.

In honor of Halloween, here are some tales from the crypts, told with help from local authors and historians Janet DeVries and Ginger Pedersen, along with archives from The Palm Beach Post and other newspapers.

Entrance to Woodlawn Cemetery

The Lurid Tale of Lena Clarke

A Jazz-era story of murder, morphine and missing money

In 1921, preacher's daughter Lena M.T. Clarke seemed to be the exemplary modern businesswoman. She was a year into her stint as West Palm Beach Postmistress. She played piano at church services and volunteered for the Red Cross.

Few of her friends or family knew the 35-year-old led a double life rife with occult dabblings, lavish spending and what The New York Times, in a front page story, called "many dubious relationships."

That summer, $32,000 was discovered missing from a registered mail sack. Suspicion centered on the new Postmistress. Clarke fled to Orlando with the law on her heels.

On a July night in her room at the luxury San Juan Hotel, she shot her former co-worker and married lover F.A. Miltimore through the heart.

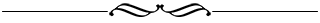

1921 newspaper photo of Lena Clarke. and F.A. Miltimore.

1921 newspaper photo of Lena Clarke. and F.A. Miltimore.

At first, she told police she only drugged him with morphine. Later, she confessed to the murder because Miltimore wouldn't take the rap for the theft.

"I did it after attempting to make him sign a statement that he had committed the robbery. He wouldn't sign and in desperation, I shot him," she told police.

The lurid tale of the flame-haired, unmarried Clarke became a sensational national story, even for the flamboyant 1920s. Newspapers of the day portrayed Prohibition-era West Palm Beach as a barely-civilized outpost, populated by Indians and rough-hewn settlers, fueled by illegal liquor and infested with dangerous animals. Writers called Clarke "a girl" and viciously described her appearance:

"Lena Mary Thankful Clarke, if you please, is a queer combination —a bundle of contradictions. In personal appearance and dress she is far from attractive. Her figure is heavy and uncorseted and her clothes smack of the backwoods.

"Her shoes are generally without heels and her stockings of cotton. Her skin is very fine in texture but covered with large, disfiguring freckles. Miss Clarke's only assets in appearance are her hair, which is decidedly Titian and naturally wavy, and her eyes, deep blue in color and absolutely straight and unwavering in their gaze," wrote one newspaper writer.

In West Palm Beach, her friends and family were astonished at the revelations about their Postmistress' after-hours cavorting with men and alcohol. After all, her mother was a member of the Women's Christian Temperance Union and her father a retired minister.

"Knowing her tendencies to avoid society and taking into consideration that she could lay small claims to personal attractiveness, people have marvelled (sic) at the reported revelings in which whiskey played an important part," wrote the Washington Times.

Clarke wasn't the only wild one in her family.

The year before, her brother, John Paul, the former Postmaster, died of a snake bite.

John Paul was a snake and alligator collector (one newspaper called him a "snake charmer") as well as a prankster. He reportedly left snakes in post office boxes to scare patrons and in mailbags, one of the reasons Miltimore gave for moving to Orlando and becoming a restaurant manager.

"(Miltimore) said it was rather annoying at times to stick his hand into a mailbox and get a handful of rattlesnakes rather than letters," an acquaintance is quoted as saying in The New York Times.

On Christmas Day 1920, John Paul died from the bite of a coral snake, which had been a Christmas present from a local Seminole Indian. Some time later, leading local citizens signed a petition recommending Clarke for her brother's job.

After her arrest in Orlando, she at first confessed to the theft and murder, then recanted. She called herself a "superwoman" who could read the sheriff's mind.

In prison, awaiting trial, she wrote poetry. A portion of one poem called "A Fool's Wisdom" included the lines:

"I told you the course you pursued was wrong

But you laughed and said women are poor, weak fools.

So I hushed on my lips my life's merry song.

To pray, while disregarded God's rules…"

A newspaper writer wrote, "Whether this poem is addressed to some human being or to her soul is not clear."

Newspaper headlines and a photo of sisters Maude (l) and Lena Clarke. (Historical Society of PB County)

At her Orlando trial in November 1921, Clarke enthralled courtroom spectators by bringing her crystal ball to court. She spun tales of leading 12 previous lives. She was in the Garden of Eden when the solar system was created, she insisted. She also claimed to have been the Egyptian goddess Isis as well as the actress for whom William Shakespeare wrote the role of Ophelia.

On December 2, 1921, jurors acquitted Clarke by reason of insanity.

She spent two years at the Chattahoochee State Hospital for the Insane, then returned to West Palm Beach where she lived with her older sister, Maude, in downtown West Palm Beach.

She resumed her charitable activities and even taught Sunday School at the Congregational Church, where her father had been pastor. She died in 1967.

Neither sister ever married. Their small gravestones rest crookedly next to each other, sinking into Woodlawn Cemetery's patchy St. Augustine grass.

The Forgotten Pioneer

Guy Metcalf's meteoric rise ended over $300

Nearly a century after he took his own life, many of the marks Guy Metcalf's life left on Palm Beach County are still visible.

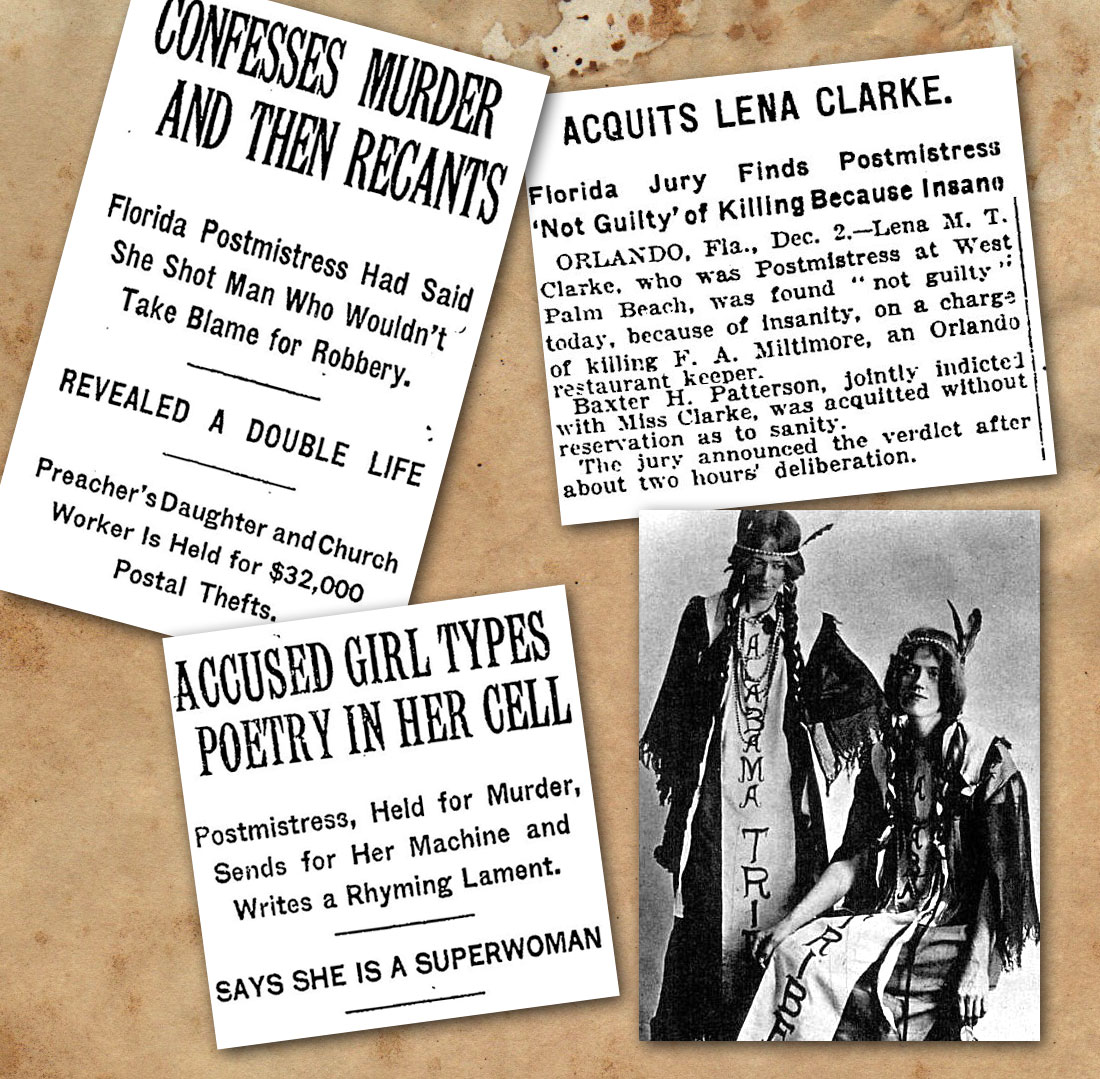

Guy Metcalf

Guy Metcalf

He campaigned for construction of the 1909 Central School, now the southernmost building at the Dreyfoos School of the Arts campus and served as the county's second school superintendent as well as West Palm Beach mayor.

A remnant of the 1892 mule-train "sand road" he built from Lantana to Lemon City (Miami) is still visible in the Hypoluxo Scrub natural area. In 1895, Metcalf brought his Tropical Sun newspaper, the forerunner to The Palm Beach Post, to West Palm Beach, making it the only South Florida paper north of Key West. Under Metcalf, the paper chronicled the settlement of the Lake Country as it became Palm Beach County.

Metcalf was school superintendent in 1918, when he was accused of misappropriating $333.49 dollars meant for school science equipment. Fearing an imminent arrest, Metcalf went to his first floor office in the 1916 courthouse building and shot himself.

The Crime of the Century

The Chillingworth murders are still chilling

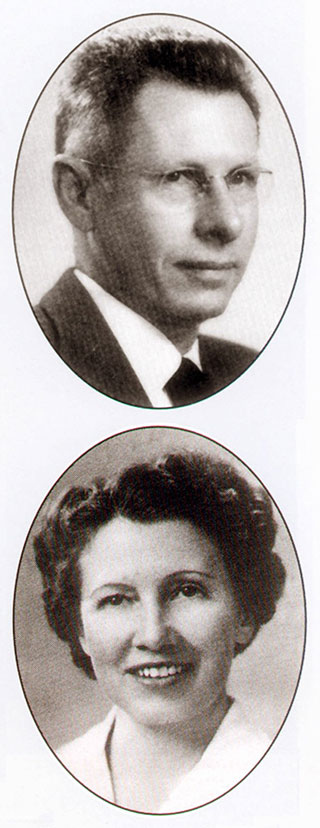

There are no bodies in the grave beneath the stone bearing the names of Judge Curtis Eugene and Marjorie Chillingworth, whose 1955 murders are known as Palm Beach County's "crime of the century."

Judge Curtis Eugene and Marjorie Chillingworth

Judge Curtis Eugene and Marjorie Chillingworth

Chillingworth was the scion of a pioneer family who was killed with his wife at the orders of another West Palm Beach judge. Municipal court judge Joe Peel was an incompetent lawyer and judge who was involved in the local bolita and moonshine rackets. He believed Chillingworth was preparing to expose him.

For $2,500, Peel hired two thugs to solve his problem. Floyd "Lucky" Holzapfel and Bobby Lincoln landed a boat on the sand of the Chillingworth's Manalapan beach house at 1 a.m. on June 14, 1955. They ordered the Chillingworths into the boat.

After motoring out to sea, they wrapped the couple in weights, giving them just enough time to say "I love you" before tossing Marjorie overboard.

"Ladies first," the murderers said.

Chillingworth jumped overboard and tried to swim, until they broke an oar over his head, sending him under the waves. Their bodies were never recovered.

The case went cold for five years, until Holzapfel bragged about the murders to a friend. In 1961, he received two life sentences after his accomplice testified against him. He was paroled nine days before he died in 1982.

Good-time Charlie

The Merrill in Merrill Lynch was well-known philanderer

The son of a backwoods country doctor from Green Cove Springs, Charles Edward Merrill was a Florida boy who ascended to the heights of the New York financial world as co-founder of Merrill Lynch & Co. in 1915 while earning the nickname "Good Time Charlie."

Charles Edward Merrill

Charles Edward Merrill

Unable to afford tuition, he dropped out of Amherst, tried law school and for a time, became a reporter for the Tropical Sun in West Palm Beach. Later in life, he said the newspaper business gave him "the best training I ever had… . (I) learned human nature."

After creating his investment firm, Merrill engineered a merger that created the Safeway grocery chain. Anticipating the 1929 stock market crash, he failed to persuade President Coolidge to discourage stock speculation, but divested his own stock before the the crash.

A well-known philanderer who regularly appeared in gossip columns, Merrill married three times and had numerous affairs, an activity he called "recharging my batteries." In Palm Beach, he owned a house on N. Lake Trail designed by Howard Major. His youngest son, the late poet James Merrill, won a 1977 Pulitzer Prize.

The Man Behind 'Palm Beach'

Brelsford was area's first postmaster

In 1880, E.M. Brelsford and his brother "Doc" came through the unsettled Lake Country on a hunting and fishing trip, becoming so enthralled with the unspoiled paradise that they bought a homestead on the east side of the lake. After establishing a general store where the Flagler Museum is today, they applied for a Post Office with the name "Palm Beach."

Mr. E.M. Brelsford and his home

E.M. became the first Postmaster. He helped found the first Bethesda Church on Lake Trail and later the first bank. In 1893, he sold his holdings to Henry Flagler.

Now prosperous beyond their wildest dreams, E.M. and his wife, Laura, built an impressive Greek Revival-style house called "The Banyans" at 1 South Lake Trail, which became the settlement's social center.

Ag Pioneers

Joe Sakai paid price for south county dream

From the beginning, sadness stalked the Yamato agricultural colony Joe Sakai began along Dixie Highway, near where Yamato Road is today. In 1903, the Japan-born, New York University-educated Sakai struck a deal with the Florida East Coast Railway to establish a colony of Japanese farmers near Boca Raton.

But heat, disease and unfamiliar food made life difficult for the Japanese immigrants and their often reluctant wives. Several children died, including Sakai's 1-year-old son, Hiroshi, the first born in the settlement. Several of the colony's settlers are buried near one another in Woodlawn.

Mr. Sakai and his family

Most of the remaining Japanese left in the 1920s. In 1942, the U.S. government confiscated any remaining Yamato land owned by Japanese settlers. Only George Morikami stayed, accumulating large holdings after World War II. He donated his property to Palm Beach County, which named a Delray Beach park and museum after him.

The Downtown Merchant

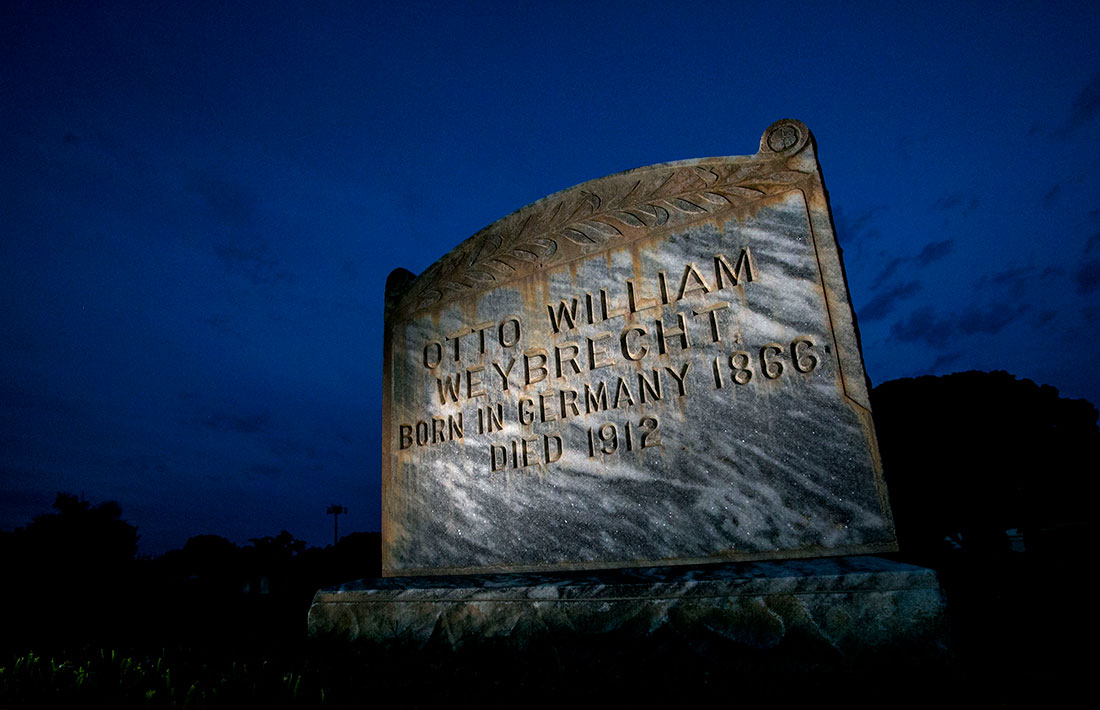

German immigrant built Clematis Street hardware store

His family lived in a tent, but German immigrant Otto William Weybrecht in 1893 built a permanent structure for his Clematis Street hardware store, the first built away from the lakefront.

Weybrecht's Hardware went up on the south side of Clematis Street, near where Rocco's Tacos is today. Two years later, much of the young city's downtown, including Weybrecht's store and the family's tent, burned to the ground. Afterward, the city required buildings be made of brick.

Weybrecht, his wife and Seminole leader Billy Bowlegs stand together in a famous early photo of what Clematis Street looked like during its pioneer period.

She Sewed Up a Fortune

Frugality helped Saunders become one of area's first female millionaires

Frugal seamstress Adah Saunders stitched together a fortune after establishing her dressmaking business on Datura Street in West Palm Beach in 1893. She made gowns for the local ladies, and spent her profits buying cheap land as the lake country frontier blossomed into a city. When the 1920s land boom arrived, she began selling property, becoming a homegrown millionaire in the process, one of the first area women to do so.

Adah Saunders, in black. (Historical Society of Palm Beach County)

Saunders reportedly once owned all the high land on the ridge from 45th Street to the city limits. She gave 30 acres of it to build what is today St. Mary's Medical Center.

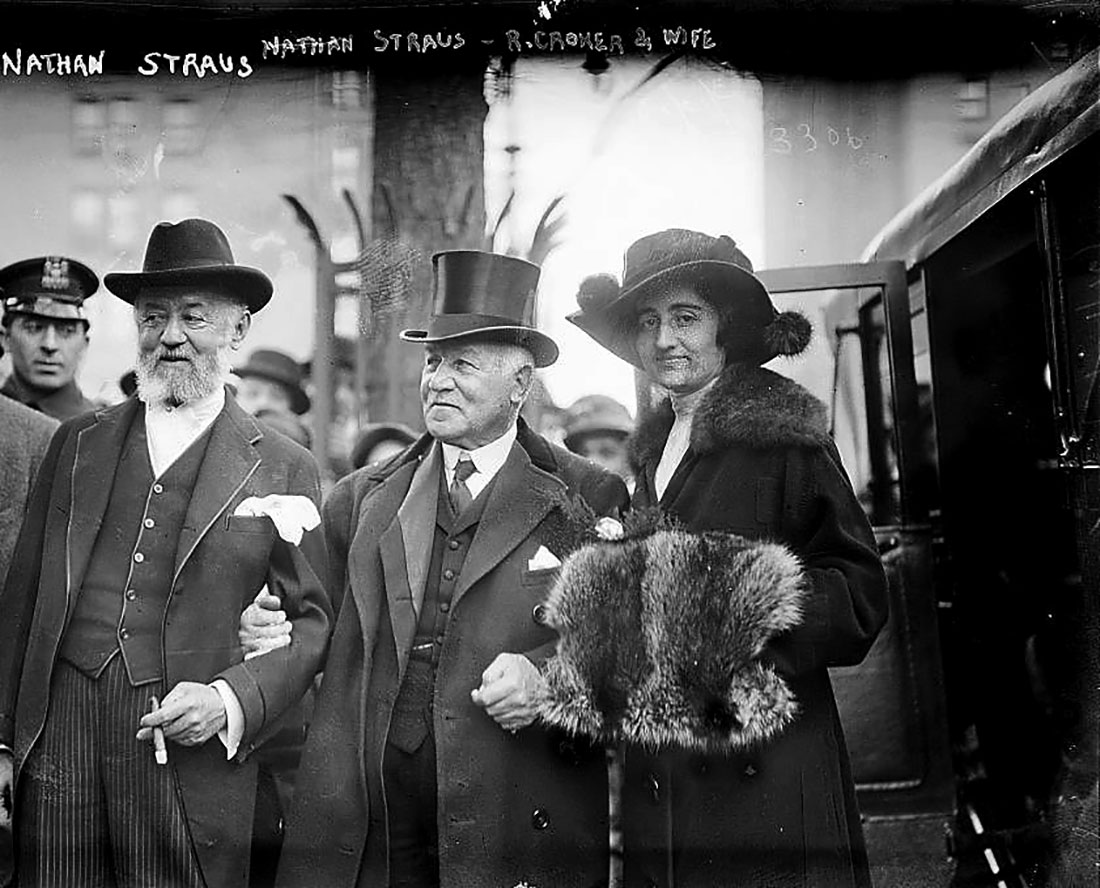

Snubbed by High Society

30-year-old Croker married 78-year-old mob boss

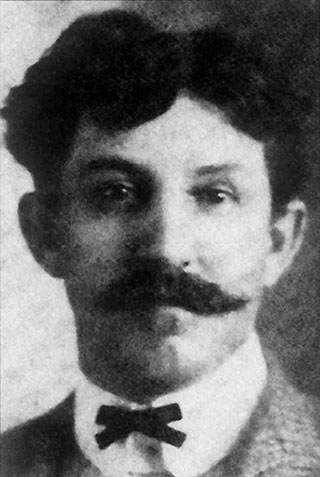

Claiming to be a Cherokee princess and descendant of Sequoyah from Oklahoma, beautiful Bula Croker attended a Cherokee college before moving to New York where at 3o, she married Richard Croker, the 78-year-old former mob boss of the Tammany Hall political machine.

In 1914, they arrived in Palm Beach where Croker owned a house with 10,000 feet of ocean frontage, south of Widener's Curve. They called it "The Wigwam." Newspaper accounts say the Indian princess and Irish mob boss husband were snubbed by Palm Beach society.

R. Nathan Strauss, Richard Croker, and Bula Edmonson Croker, 1914, New York. (Library of Congress)

Her crypt looms mysteriously under one of Woodlawn's large banyan trees, with no birth or death dates visible. Historian Ginger Pedersen has occasionally found pennies laid on the tomb's stoop.

After her husband died in Ireland in 1922, Bula unsuccessfully sought a Florida Congressional seat, while fighting her step-children for the right to inherit her husband's estate. At one point, she was near destitute. She sold off portions of "The Wigwam" in 1937; the house was torn down years later.

Barefoot Mailman 2.0

Pierce walked the beaches to deliver letters

In 1873, Hannibal Pierce, a Union Civil War veteran, filed the second homestead in what was known as the Lake Country. His son Charlie Pierce grew up on wild, untamed Hypoluxo Island in what is now Lantana before the area had any roads. Charlie Pierce became the area's second "barefoot mailman," walking 136 barefoot miles round trip along the beach from Hypoluxo to Ft. Dallas (Miami) to deliver the mail. The service ran from 1883 to 1893. Later, Pierce became a boat captain who delivered freight and passengers up and down the coast.

Later in life, Pierce wrote "Pioneer Life in Southeast Florida," a definitive account of life on the Florida frontier.

In the 1930s, the original Pierce homestead was sold to Consuelo Vanderbilt, the former Duchess of Marlborough and her husband, Jacques Balsan, who built a mansion called Casa Alva on the property. The Pierce house became part of the servants' quarters.

The Mass Grave

White victims of 1928 hurricane buried at Woodlawn

After a 1928 hurricane swept across Lake Okeechobee, drowning perhaps more than 3,000 people, victims were loaded on trucks and mule wagons and brought to the coast. Water lay so thick over the muck that burials would not be possible for months. After days in the sun, identification of victims was impossible. Fearful of disease, officials buried bodies as quickly as possible.

In those Jim Crow days, white victims were buried in Woodlawn Cemetery, while blacks were taken to a site at Tamarind Avenue and 25th Street. About 69 whites are reportedly buried in a mass grave beneath this eroding marker. Approximately 674 blacks were interned at the 25th Street site.

A Woodlawn Grave Tour

Historians Janet DeVries and Ginger Pedersen's favorite pasttime is wandering through area graveyards and wondering about the early settlers buried there. Their latest book, "Legendary Locals," profiles 100 heroes and villians from pioneers to those living today who have shaped the country's last frontier into modern Palm Beach County.

"The stories are so rich," said DeVries. "Some have been forgotten and others gnaw at your heart."

The book, which will be released November 30, will be available locally at The Classic Book Shop in Palm Beach, The Liberty Book Store in downtown West Palm Beach, Barnes and Nobles stores in Palm Beach County and on Amazon; $21.99.

DeVries and Pederson will also be conducting tours of Woodlawn Cemetery once a month through May. For required reservations call all 561-804-4900. A $5 donation appreciated. Wear closed shoes, bring a flashlight and bug spray.

Nov., 25, Dec. 23, Jan. 22, Feb. 22, all at 6:30 p.m.

March 23, April 21 and May 20 at 7:30 p.m.

If You Go

Woodlawn Cemetery

Where: 1301 S. Dixie Highway, West Palm Beach

Information: wpb.org